Hopefully the Most Gentle Introduction to Simulation

A good portion of this content was originally the first set of notes for a course I took, called Topics in Computer Graphics: Seminar on Physics Based Animation mainly as an excercise to remind myself of the basic ideas when I was taking the course. I would credit a lot of this content to the course.

Arguably the primary areas of computer graphics are,

- modelling: geometric and appearance properties to store on computers

- rendering: modelling how light interacts with the world and making images

- animation: concerned with motion

But animation is not always just motion; it could also be, for instance, sound. In general, we somehow need to find ways to generate complex motions from simple rules.

Simulation or physics-based animation (atleast for the purpose of this article) has a very interesting goal: to predict the future or past of a system based on the current state of the system, so if we know some initial state of the system fully and we know the law that it satisfies we can predict the future or past.

An important distinction here is state. If you consider a particle with some motion, the future is not just defined by the the current “position” or configuration but rather it is uniquely determined by the state1 of the system2.

Before we start, a quick map of viewpoints. Newtonian, Lagrangian, and Hamiltonian are three mathematical models on the same dynamics. Newtonian talks in forces and accelerations. Lagrangian talks in energies and picks the motion that best balances them. Hamiltonian talks in positions and momenta and tracks how energy flows. Here we use the Lagrangian view because it plugs cleanly into meshes, springs, and hard constraints and turns into linear‑algebra formulas we can code. Hamiltonian has has a very nice geometric interpretation (and I actually feel this view is more natural and intuitive) and the symplectic structure is totally canonical (whereas integrators can drift energy).

Springs are Everywhere!

When something prefers a rest shape, length, or angle and resists being changed, you can model that preference as a “spring.” In practice we attach many small, virtual springs to the parts of an object that we want to keep under control. Each spring gently pulls the system back toward a desired state; the collection of all these pulls produces realistic motion.

We can simulate cloth or deformable shapes or rigid shapes by having many-many small mass-spring systems inside the shape. After all rigidity can be seen as the limit of extremely stiff springs that forbid shape change.

Newton’s Law

Let us say we have a particle; it has a bunch of properties:

- $\color{#17becf}{x(t)}$: position in space

- $\color{#1f77b4}{v(t)} = \color{#1f77b4}{\frac{dx}{dt}} (t)$: velocity in space

- $\color{#d62728}{a(t)} = \color{#d62728}{\frac{d^2x}{dt^2}} (t)$: acceleration in space

- $\color{#7f7f7f}{m}$: mass

The momentum is $\color{#8c564b}{p} = mv$. Newton’s second law says the time rate of change of momentum $\frac{d}{dt} (mv)$ is the force $\color{#ff7f0e}{f}$. Assuming we have a constant mass, $\color{#7f7f7f}{m} \, \color{#d62728}{\frac{dv}{dt}} = \color{#ff7f0e}{f}$. This is called vectorial mechanics.

We are more interested in variational mechanics or analytical mechanics3, which is based on two fundamental energies (kinetic and potential) rather than these vector properties. Here, motion is defined using a variational principle, \begin{equation} e\big(f(t), \, \dot f(t), \ldots\big) \;\longrightarrow\; \mathbb{R}, \end{equation} where $e$ is a functional, and $f(t), \dot f(t), \ldots$ are functions of time and their derivatives.

Generalized Coordinates

One thing we need for variational mechanics is generalized coordinates4. $\color{#17becf}{q(t)}$ are coordinates we use in our simulation, and a function $f$ translates these into world coordinates: \begin{equation} \color{#17becf}{x(t)} = f(\color{#17becf}{q(t)}). \end{equation} We can get velocity by the chain rule5, \(\begin{equation} \color{#1f77b4}{\frac{dx}{dt}} (t) = \overbrace{\color{#8c564b}{\frac{df}{dq}}}^{\color{#8c564b}{\text{Jacobian}}} \underbrace{\color{#1f77b4}{\dot q(t)}}_{\color{#1f77b4}{\text{generalized velocity}}}. \end{equation}\) For example, a particle moving in space: $x(t) = q(t) \in \mathbb{R}^3$ can represent the position of the center of the particle, in which case the Jacobian is the identity. Another example is adding rigid motion: \(x(t) = \underbrace{RX + p}_{q}\), where \(\underbrace{R \in SO(3)}_{3\times 3\, \text{matrix}}\) and $p \in \mathbb{R}^3$.6

Lagrangian

\[\begin{equation} \underbrace{\color{#bcbd22}{L}}_{\color{#bcbd22}{\text{Lagrangian}}} = \overbrace{\color{#2ca02c}{T}}^{\color{#2ca02c}{\text{KE}}} - \underbrace{\color{#9467bd}{V}}_{\color{#9467bd}{\text{PE}}}. \end{equation}\]Let us say we have two times and the particle passes from one to the other. Leibniz conjectured that we could find the path between them by finding a stationary point of the action7. The action is a functional mapping $q$ and its time derivative to a scalar value, i.e. the integral of the Lagrangian over time:

\begin{equation}

\color{#e377c2}{S}(q(t), \dot q(t)) = \int_{t_1}^{t_2} \big( T(q(t), \dot q(t)) - V(q(t), \dot q(t)) \big)\, dt.

\end{equation}

We can minimize by finding a flat spot by perturbing the trajectory and seeing whether $\color{#e377c2}{S}$ changes:

\begin{equation}

\color{#e377c2}{S}(q + \delta q, \dot q + \delta \dot q) = \color{#e377c2}{S}(q(t), \dot q(t)).

\end{equation}

Then these are the correct solutions. But how do you find $q$? This is where the calculus of variations comes in:

\begin{equation}

\begin{split}

\color{#e377c2}{S}(q(t), \dot q(t)) &= \int_{t_1}^{t_2} L(q(t), \dot q(t))\, dt, \\\

\color{#e377c2}{S}(q + \delta q, \dot q + \delta \dot q) &= \int_{t_1}^{t_2} L(q + \delta q, \dot q + \delta \dot q)\, dt.

\end{split}

\end{equation}

Now apply a Taylor expansion inside the integral,8

So all you need to do is find $q$ for which the first variation is $0$:

\[\begin{equation} \int_{t_1}^{t_2} \frac{\partial L}{\partial q}\, \delta q + \underbrace{\frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot q}\, \delta \dot q}_{\text{Integration by parts}}\, dt = 0. \end{equation}\]This allows us to eliminate the perturbation on $\dot q$,

\[\begin{equation} \int_{t_1}^{t_2} \frac{\partial L}{\partial q}\, \delta q - \frac{d}{dt}\frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot q}\, \delta q\, dt + \underbrace{\left. \frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot q} \, \delta q \right\vert^{t_2}_{t_1}}_{\text{boundary conditions}} = 0. \end{equation}\]We impose fixed endpoints at $t_1$ and $t_2$, so the perturbation vanishes there: $\left. \frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot q}\, \delta q \right\vert^{t_2}_{t_1} = 0$. Thus,

\[\begin{equation} \int_{t_1}^{t_2} \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial q} - \frac{d}{dt} \frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot q} \right) \delta q\, dt = 0. \end{equation}\]Our perturbation is arbitrary, so the integrand must always be zero:

\[\begin{equation} \overbrace{\frac{d}{dt}\frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot q} = - \frac{\partial L}{\partial q}}^{\text{Euler–Lagrange equation}}. \end{equation}\]If a trajectory satisfies Euler–Lagrange, then it is physically valid. 9

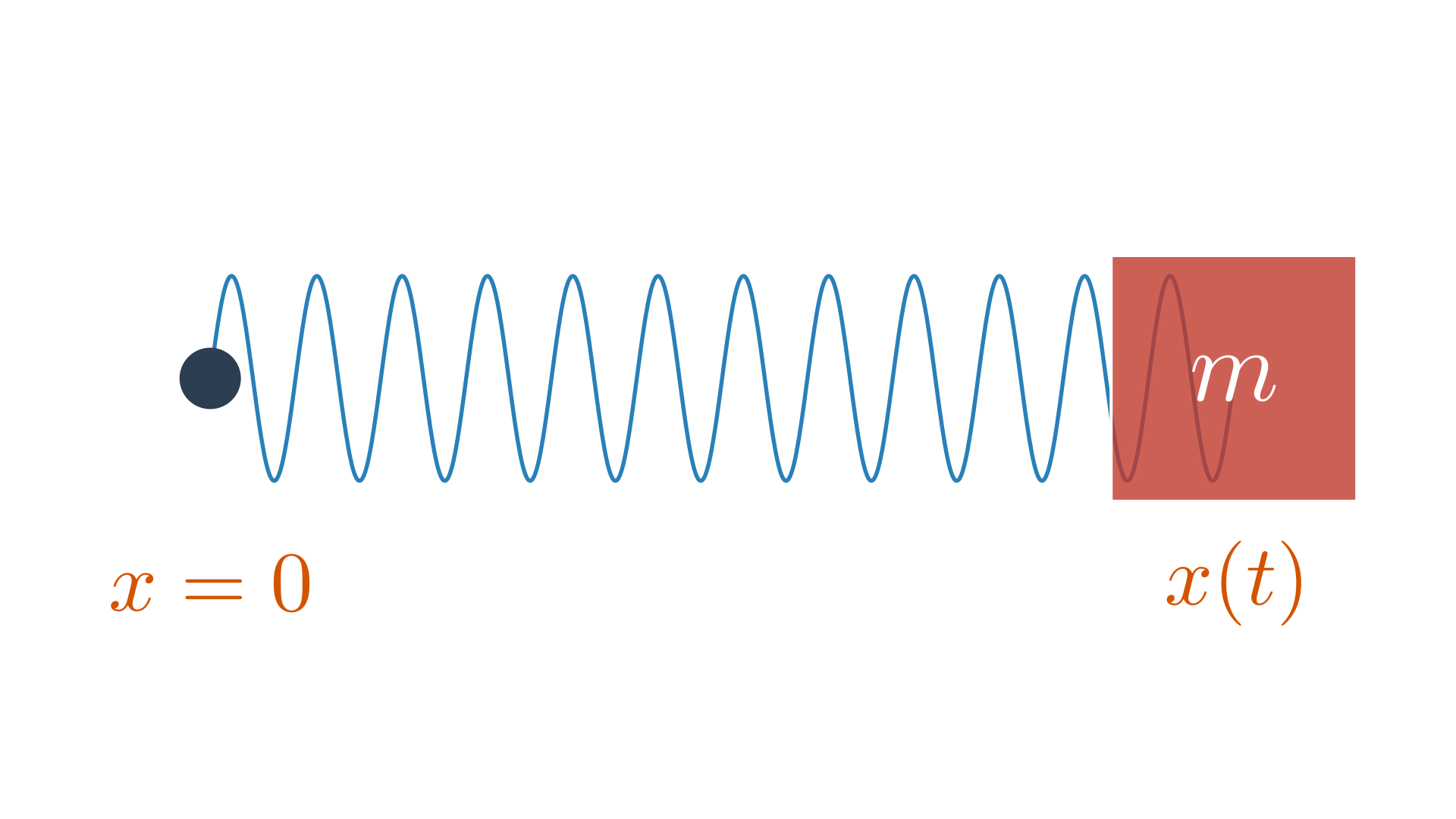

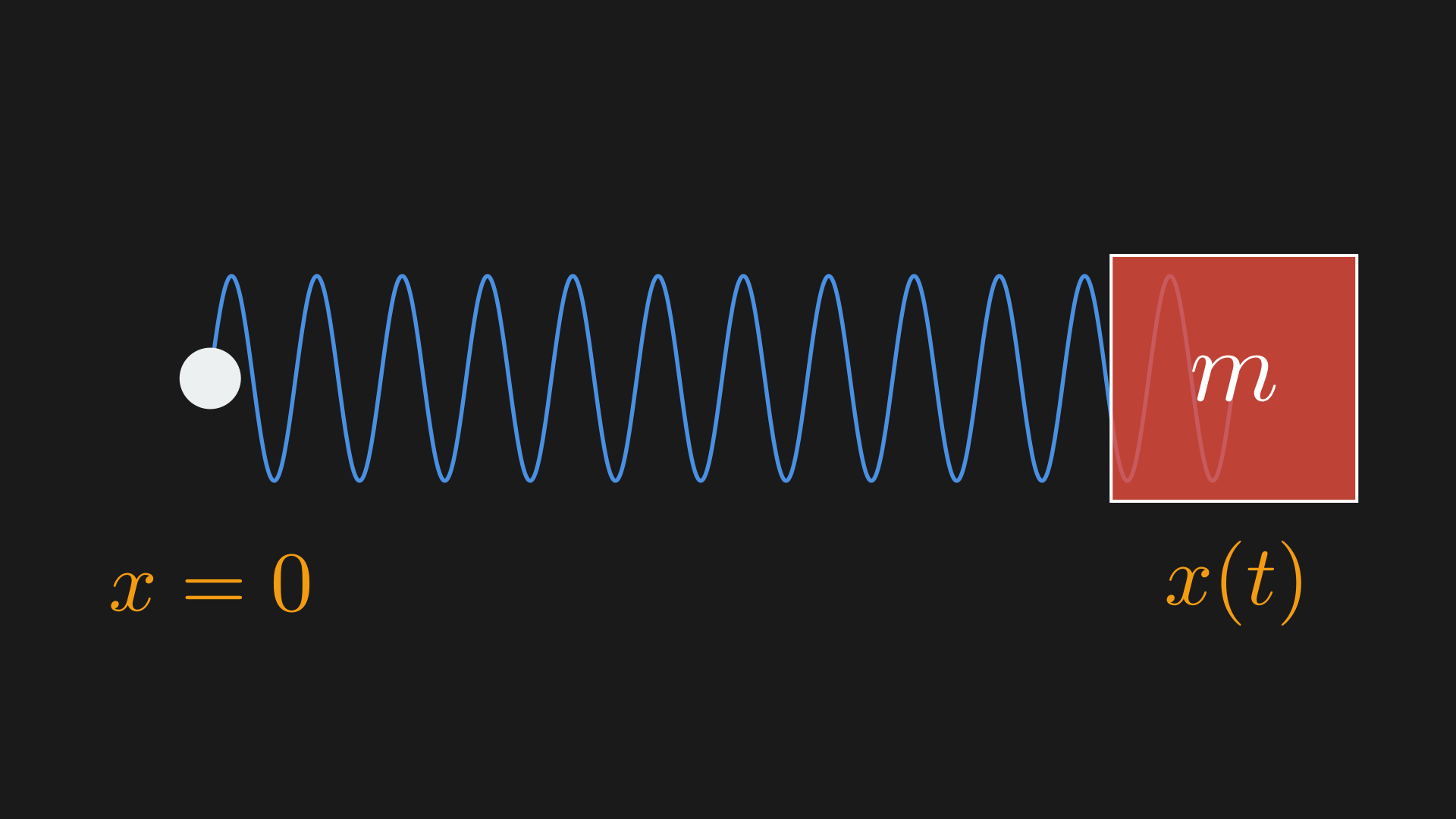

Mass–Spring System (1D)

In 1D, the kinetic energy is $T = \tfrac{1}{2} m \dot q^2$.

Since potential energy is the negative of mechanical work,

\begin{equation}

W = \int -k\, x(t)\, v(t)\, dt = \int -k\, x\, dx = -\tfrac{1}{2} k x^2 \;\implies\; V = \tfrac{1}{2} k q^2.

\end{equation}

Thus,

\begin{equation}

\begin{split}

L &= \tfrac{1}{2} m \dot q^2 - \tfrac{1}{2} k q^2, \\\

\frac{d}{dt}\frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot q} &= \frac{d}{dt} (m \dot q), \\\

\frac{\partial L}{\partial q} &= -k q.

\end{split}

\end{equation}

Using Euler–Lagrange:

\begin{equation}

m \ddot q = -k q.

\end{equation}

Time Integration

Newton’s law, $m \ddot q = f(q)$, is a second-order ODE; it gives local information about curvature on a $t$ vs $q$ graph. Time integration generates the full function $q$ over time. Thus, generating an animation is equivalent to traversing this curve in time.

Input. An ODE, $\ddot q = f(q, \dot q)$ and initial conditions: $q_0 = \mathbf{q}(t_0)$, $\dot q_0 = \mathbf{\dot q}(t_0)$.

Output. A discrete update equation $\mathbf{q}^{t+1} = F(\mathbf{q}^t, \mathbf{q}^{t-1}, \ldots, \mathbf{\dot q}^t, \mathbf{\dot q}^{t-1}, \ldots)$.

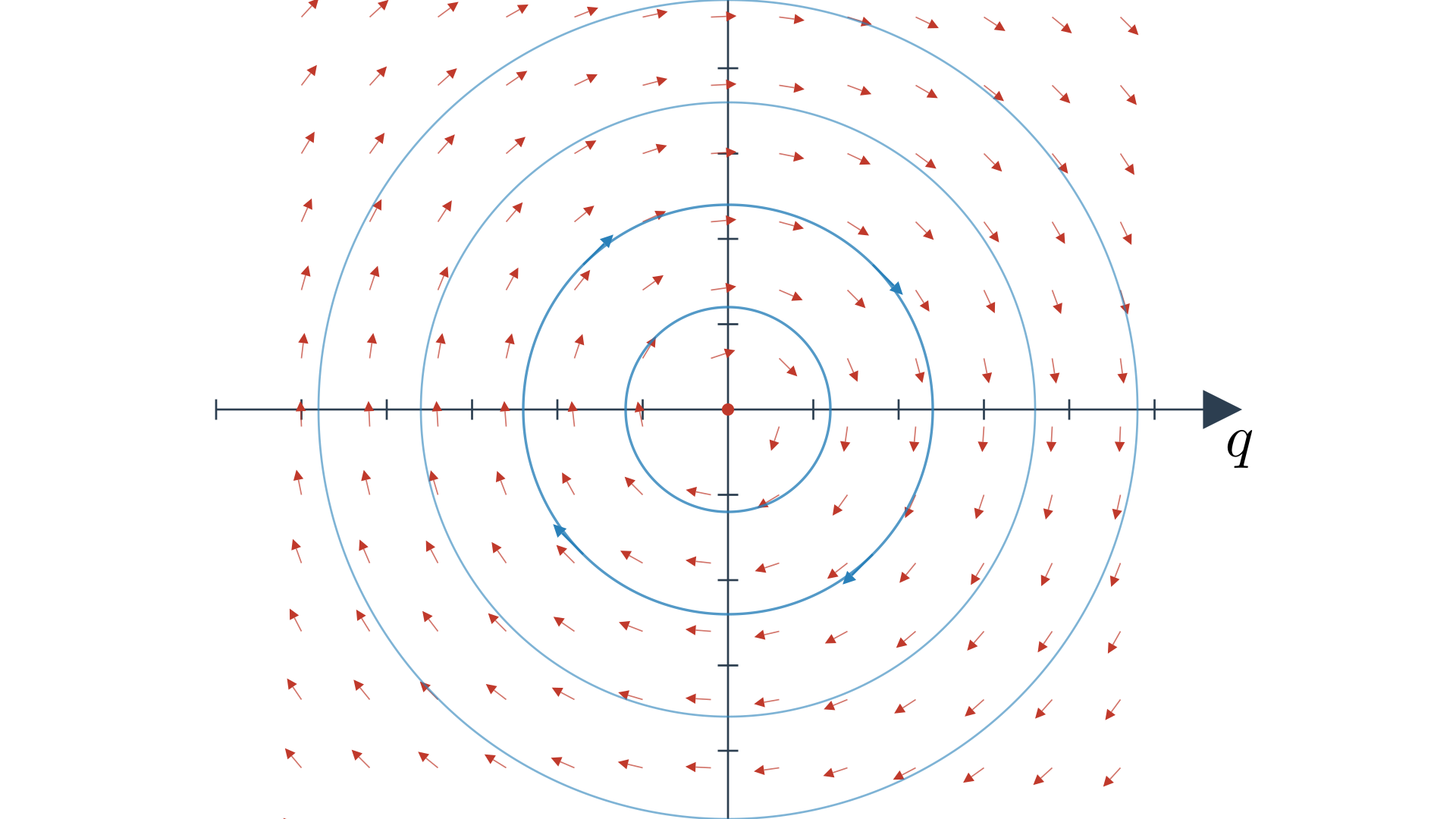

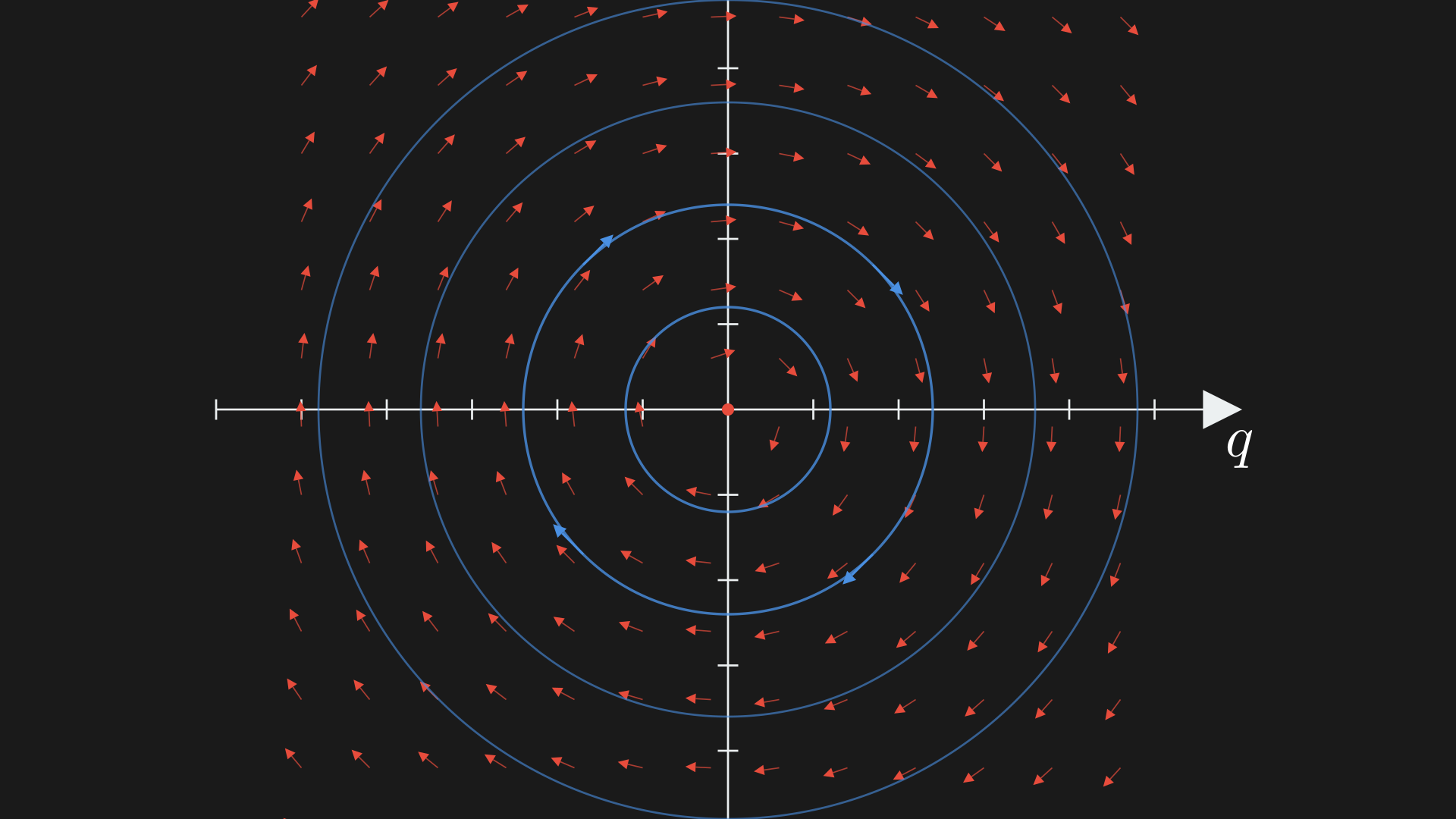

Let us do this for the mass–spring system. We have a second-order ODE $m \ddot q = -k q$. Set $\dot q = v$ to get a first-order system $m \dot v = -k q$. In matrix form,

\[\begin{equation} \underbrace{\begin{pmatrix} m & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}}_{A} \underbrace{\frac{d}{dt} \begin{pmatrix} v \\ q \end{pmatrix}}_{\dot y} = \overbrace{\begin{pmatrix} 0 & -k \\ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix} \underbrace{\begin{pmatrix} v \\ q \end{pmatrix}}_{y}}^{f(y)} \;\implies\; A \dot y = f(y). \end{equation}\]We can see that our ODE defines the vector field in the phase plane and the integration is a circle in this simple case.10

There are two types of time integration algorithms:

- explicit: the next time step uses only values at or before the current time

- implicit: the next time step uses values at the future time (solved implicitly)

Forward Euler Time Integration

Approximate the derivative with a first-order finite difference,

\begin{equation}

\dot y \approx \frac{1}{\Delta t} (y^{t+1}-y^t).

\end{equation}

Evaluate the function $f$ at the current timestep,

\begin{equation}

A \, \frac{1}{\Delta t} (y^{t+1}-y^t) = f(y^t) \;\implies\; y^{t+1} = y^t + \Delta t\, A^{-1} f(y^t).

\end{equation}

Now expand into individual update rules,

\begin{equation}

\begin{split}

v^{t+1} &= v^t - \Delta t \, \frac{k}{m} q^t, \\

q^{t+1} &= q^t + \Delta t \, v^t.

\end{split}

\end{equation}

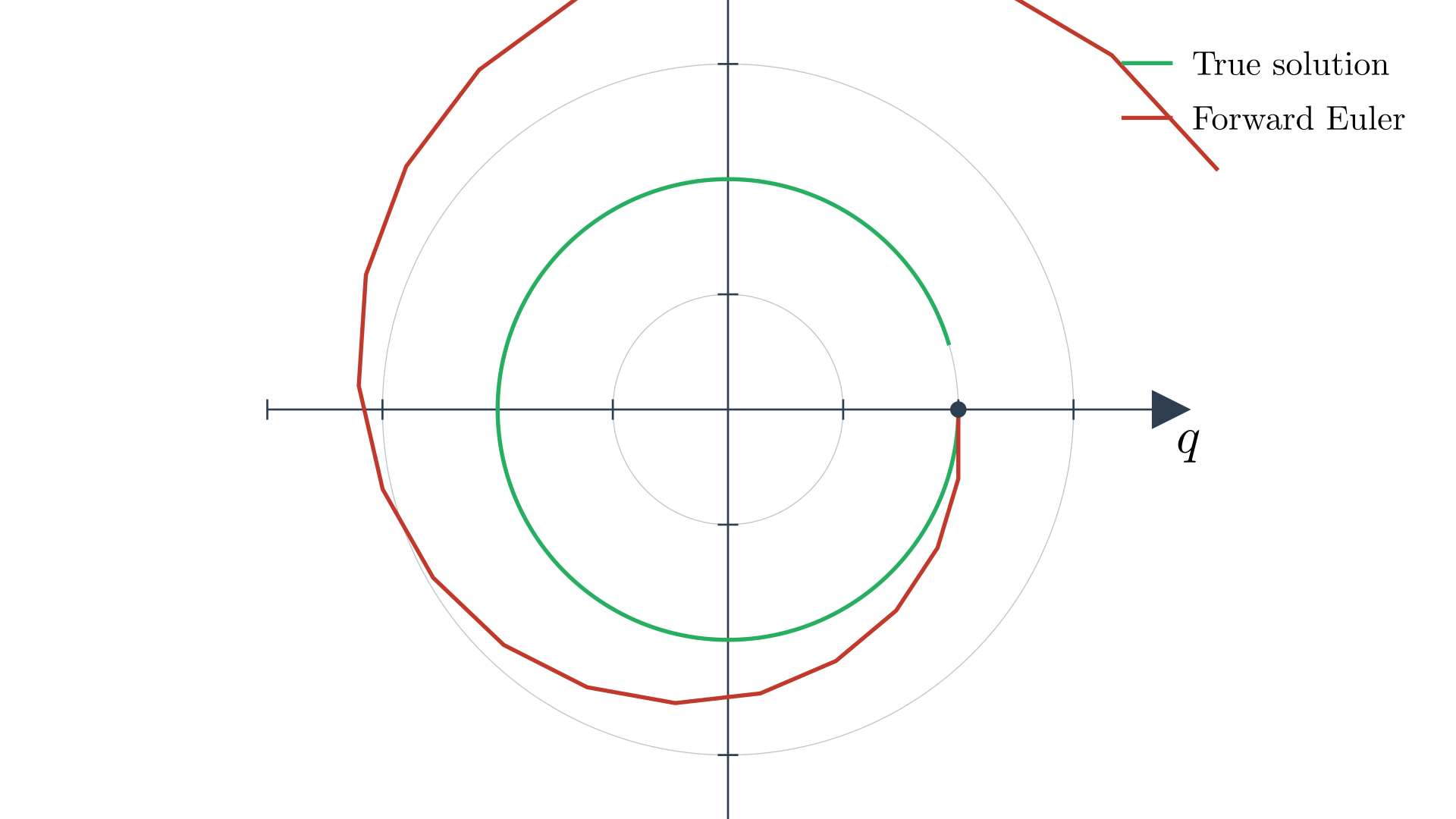

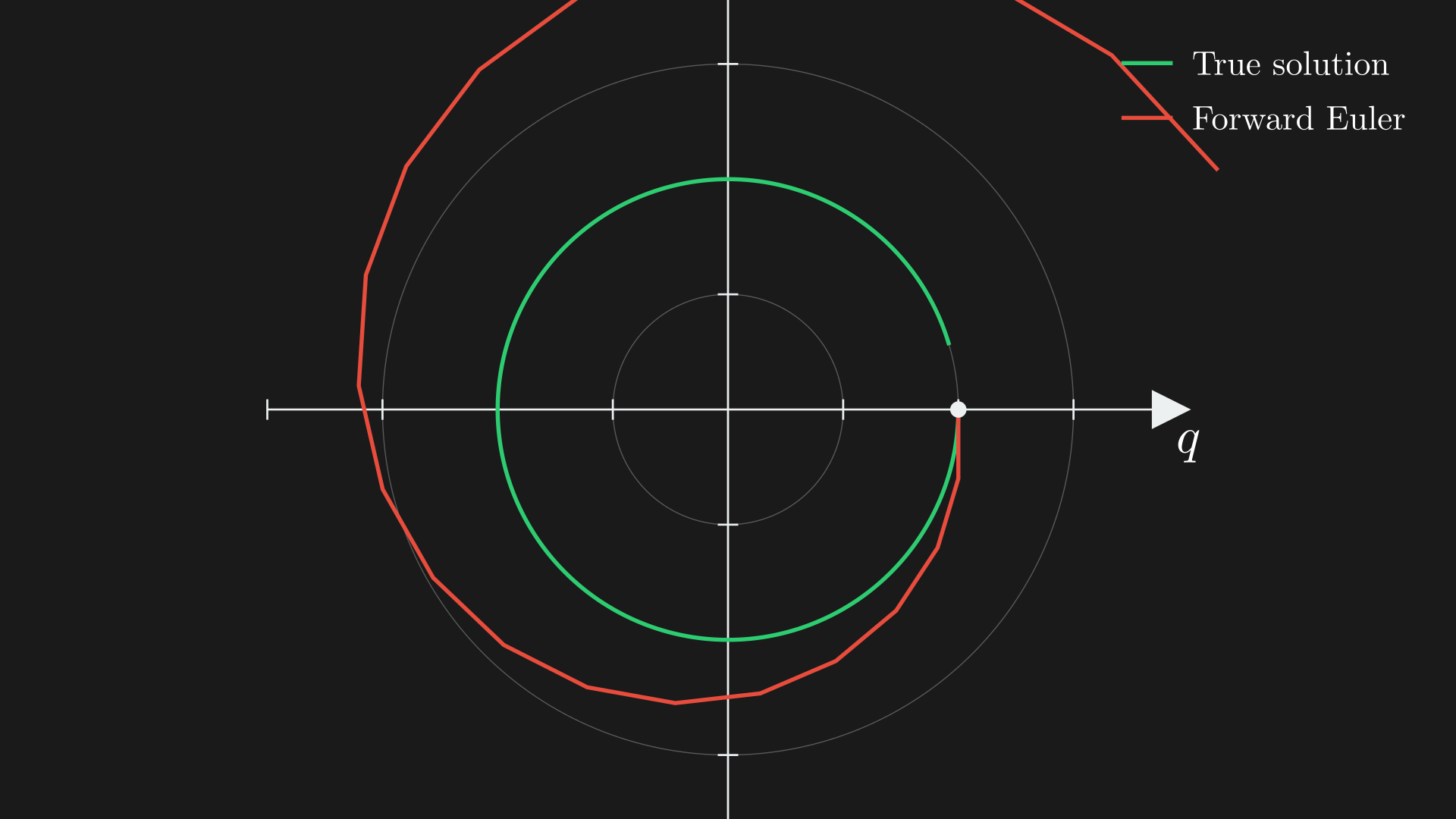

Forward Euler is not numerically stable here; it spirals outwards (unbounded).11

Runge–Kutta Time Integration

Main idea: rather than using a single slope like Forward Euler, use multiple slopes.12

\(\begin{equation} y^{t+1} = y^t + \Delta t\\, A^{-1} \big( \alpha \\, \underbrace{f\big(y^{t+\overbrace{a}^{\text{time coefficient}}}\big)}_{\text{slope 1}} + \beta \\, \underbrace{f\big(\tilde y^{\\, t+\overbrace{b}^{\text{time coefficient}}}\big)}_{\text{slope 2}} \big). \end{equation}\) $y^{t+a}$ and $y^{t+b}$ are estimates at future timesteps obtained via Forward Euler, $\tilde y^{\, t+a} = y^t + a\, \Delta t\, A^{-1} f(y^t)$. $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are averaging coefficients.

A good choice is $a=0$, $b=1$, $\alpha=\beta=\tfrac{1}{2}$. With these we get Heun’s method, \begin{equation} y^{t+1} = y^t + \frac{\Delta t}{2} A^{-1}\big(f(y^t) + f(\tilde y^{\, t+1})\big), \qquad \tilde y^{\, t+1} = y^t + \Delta t \, A^{-1} f(y^t). \end{equation}

One of the most popular approaches is fourth-order Runge–Kutta (RK4), which is quite stable,

\begin{equation}

\begin{split}

\kappa_1 & = A^{-1} f\big(y^t\big), \\

\kappa_2 & = A^{-1} f\big(y^t+\tfrac{\Delta t}{2} \, \kappa_1\big), \\

\kappa_3 & = A^{-1} f\big(y^t+\tfrac{\Delta t}{2} \, \kappa_2\big), \\

\kappa_4 & = A^{-1} f\big(y^t+\Delta t \, \kappa_3\big), \\

\mathbf{y}^{t+1} &= \mathbf{y}^t + \frac{\Delta t}{6}\left(\kappa_1+2\kappa_2+2\kappa_3+\kappa_4\right).

\end{split}

\end{equation}

Backward Euler Time Integration

Start the same way as before, but evaluate the force at the next time step, \begin{equation} A \, \frac{1}{\Delta t}\left(y^{t+1}-y^t\right) = \underbrace{f\left(y^{t+1}\right)}_{\text{evaluated at next time step}}. \end{equation} However, unlike Runge–Kutta we do not use Forward Euler to get $y^{t+1}$; we truly do an implicit integration.

Let us make some notation to show that this is linear in $y$:

\[\begin{equation} \underbrace{\begin{pmatrix} m & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}}_{A} \underbrace{\frac{d}{dt} \begin{pmatrix} v \\ q \end{pmatrix}}_{\dot y} = \overbrace{\underbrace{\begin{pmatrix} 0 & -k \\ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}}_{B} \underbrace{\begin{pmatrix} v \\ q \end{pmatrix}}_{y}}^{f(y)} \;\implies\; A \dot y = B y. \end{equation}\]Now write Backward Euler as

\[\begin{equation} A \, \frac{1}{\Delta t}\left(y^{t+1}-y^t\right) = \underbrace{B\, y^{t+1}}_{\text{evaluated at next time step}}. \end{equation}\]Let us now write the update rule and simplify it,

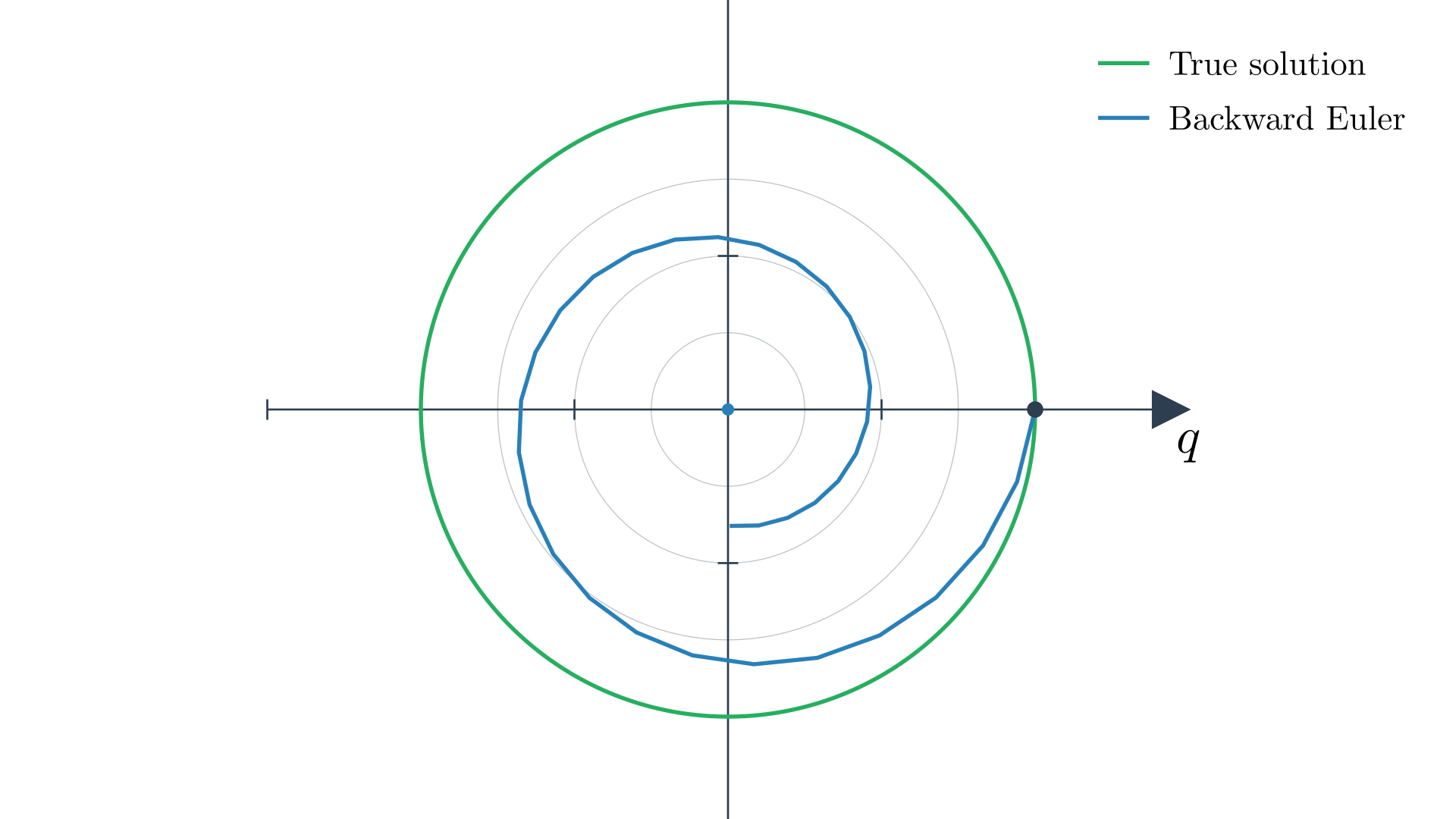

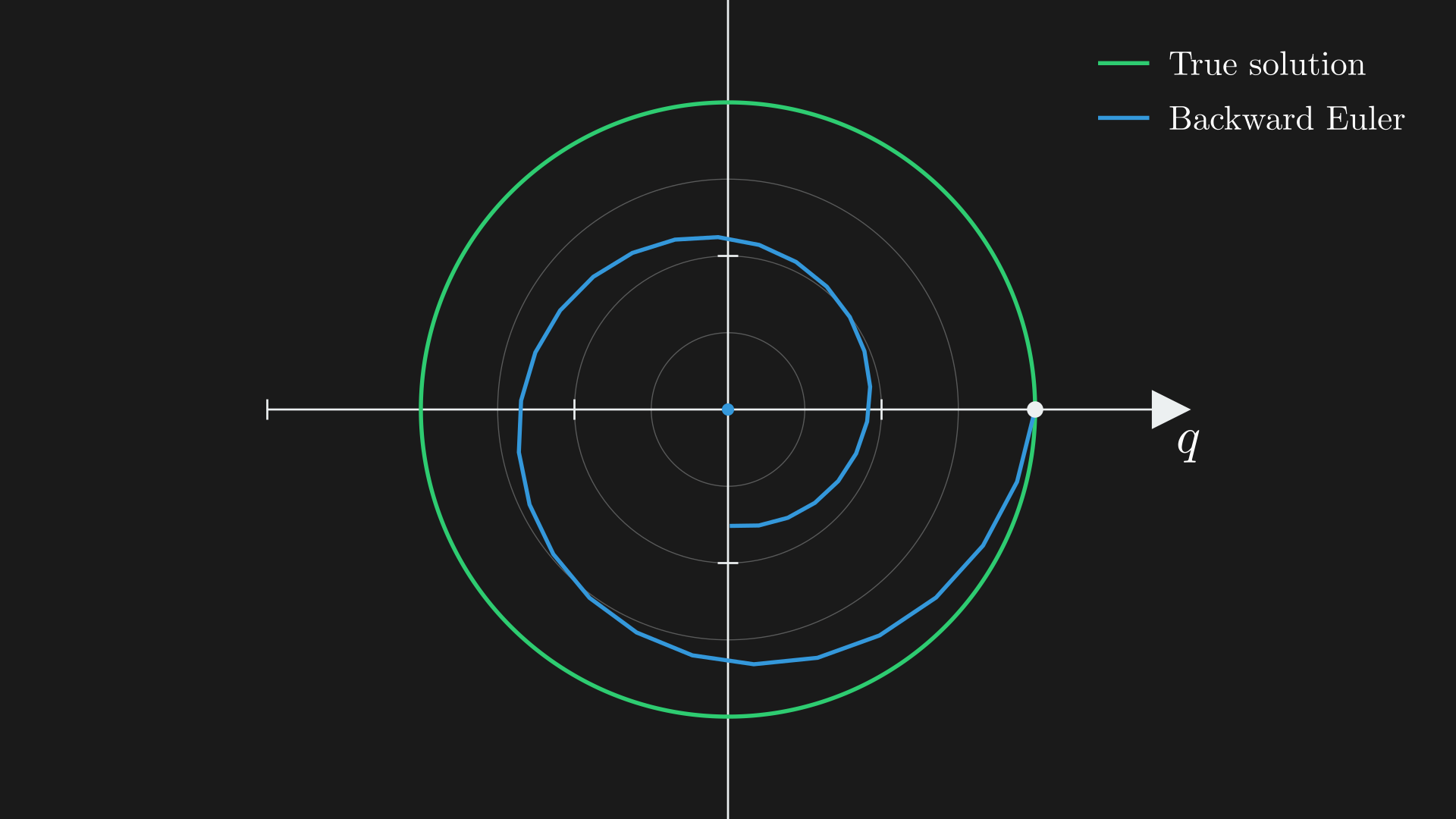

\[\begin{equation} \begin{split} y^{t+1} &= y^t + \Delta t\, A^{-1} B\, y^{t+1}, \\ (\mathbb{I}-\Delta t\, A^{-1} B)\, y^{t+1} &= y^t. \end{split} \end{equation}\]We can also write this in the following way, which will be useful for some analysis, \begin{equation} \underbrace{y^{t+1}-y^t}_{\text{vector between states}} = \overbrace{\Delta t\, A^{-1} B\, y^{t+1}}^{\text{slope at } t+1}. \end{equation} As in the phase portrait, Backward Euler slowly converges to the origin, where the block is at the wall with zero velocity and has lost all its energy. This damping is numerical, not physical; it makes the algorithm unconditionally stable, and can help model real-world damping effects.13

We can represent Backward Euler in terms of generalized position $q$ and velocity $v$,

\begin{equation}

\begin{split}

& (\mathbb{I}-\Delta t\, A^{-1} B)\, y^{t+1}=y^t, \\\

& v^{t+1}+\Delta t\, \frac{k}{m} \, q^{t+1}=v^t \quad\quad q^{t+1}-\Delta t\, v^{t+1}=q^t, \\\

& v^{t+1}+\Delta t\, \frac{k}{m}\left(q^t+\Delta t\, v^{t+1}\right)=v^t \;\text{ (by plugging in $q^{t+1}-\Delta t\, v^{t+1}=q^t$)}, \\\

& \left(1+\Delta t^2 \, \frac{k}{m}\right) v^{t+1}=v^t-\Delta t \, \frac{k}{m} \, q^t \quad\quad q^{t+1}=q^t+\Delta t\, v^{t+1}.

\end{split}

\end{equation}

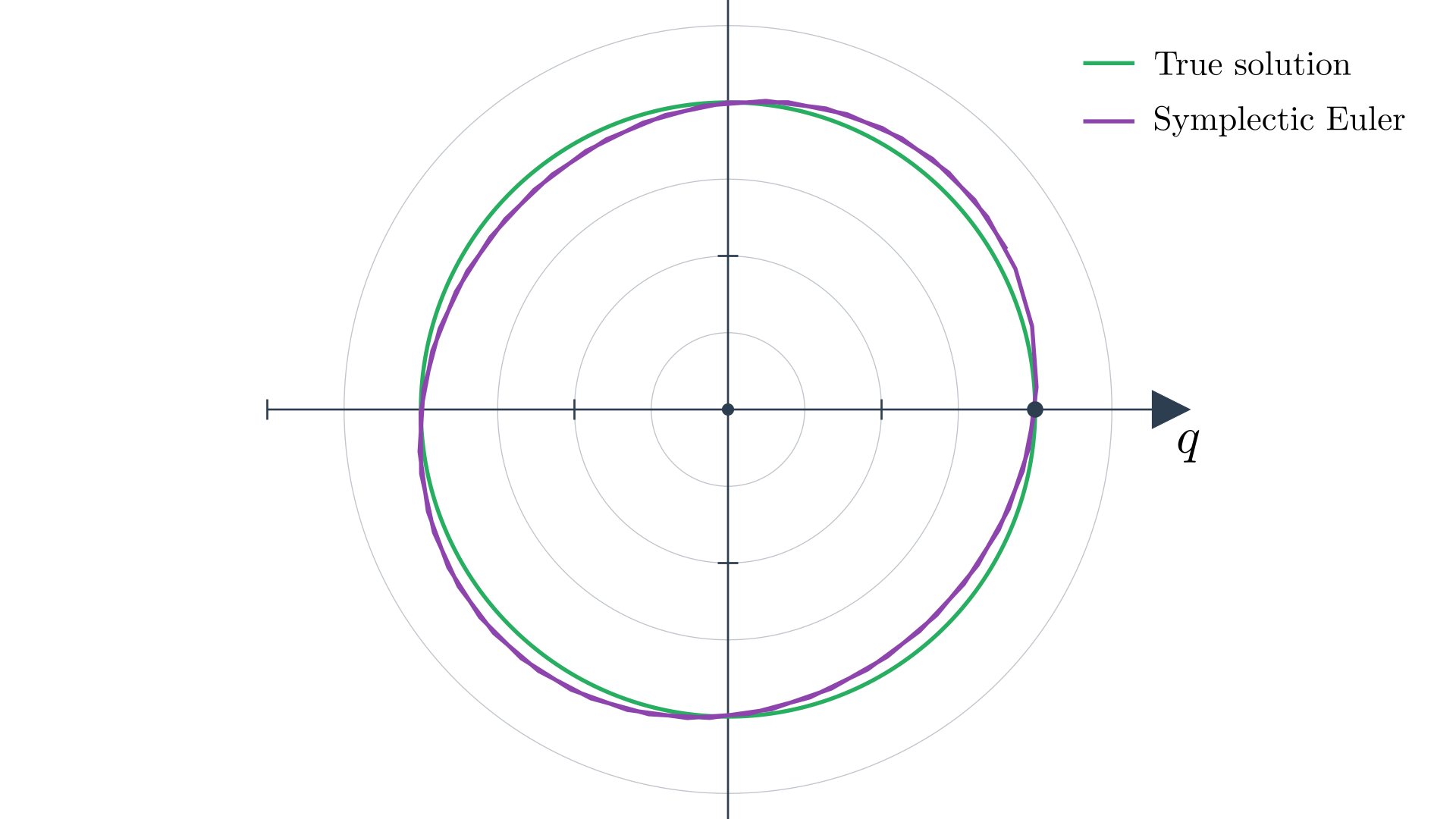

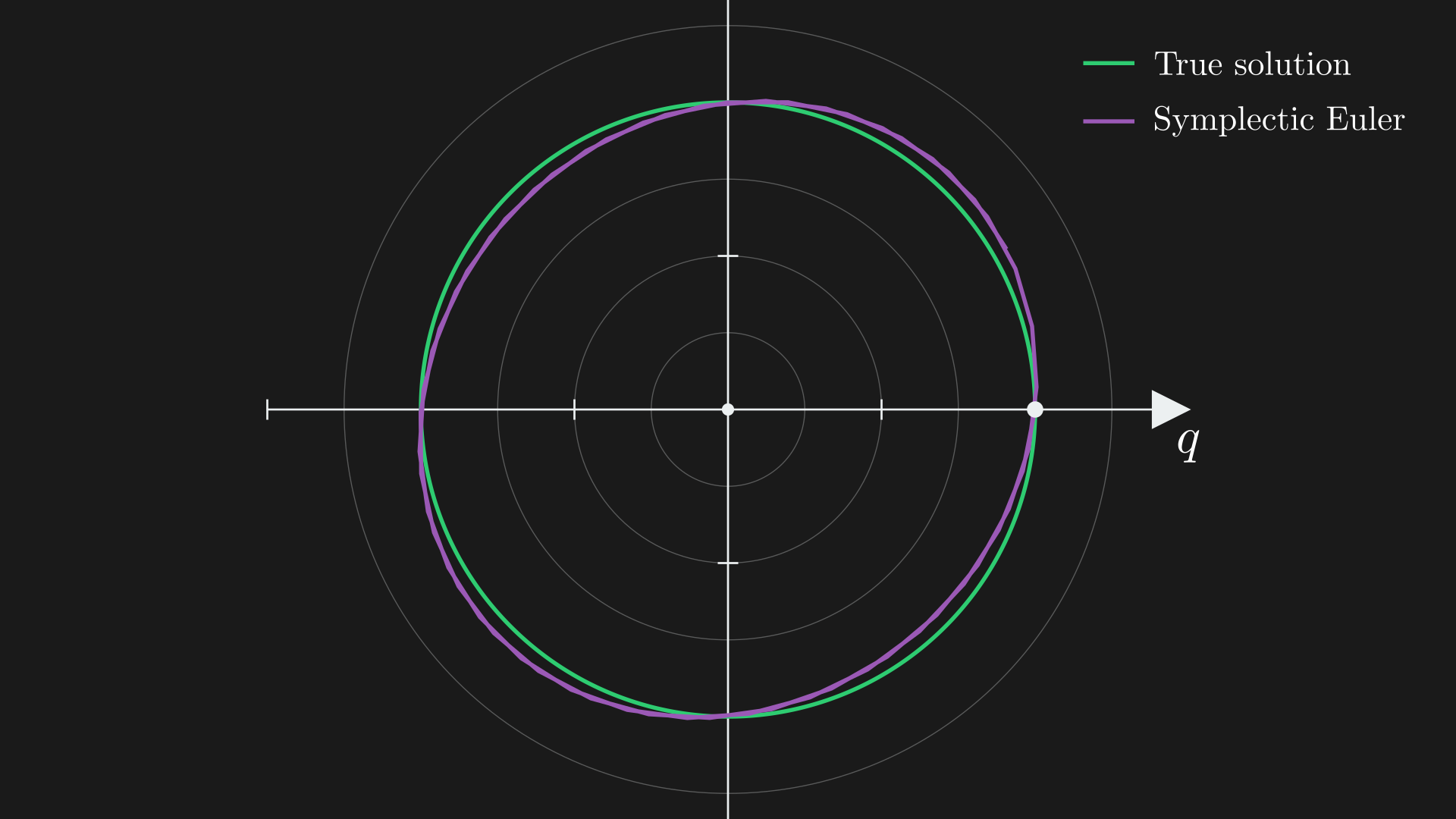

Symplectic Euler Time Integration

- First take an explicit velocity step \begin{equation} v^{t+1}=v^t-\Delta t \, \frac{k}{m} \, q^t. \end{equation}

- Next take an implicit position step \begin{equation} q^{t+1}=q^t+\Delta t \, v^{t+1}. \end{equation} If we do this just right, we can cancel the exploding and damping. A property is that our simulation can survive until infinity if we do this.

Mass–Spring Systems in 3D

We can first get generalized coordinates and generalized velocity of the spring–mass system. Suppose there are two particles at positions $\color{#17becf}{x_0}$ and $\color{#17becf}{x_1}$ at the two ends of the spring, \begin{equation} \dot q = \begin{pmatrix} \dot x_0 \\\ \dot x_1 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} v_0 \\\ v_1 \end{pmatrix}. \end{equation} Thus the kinetic energy is $\tfrac{1}{2} m \lVert v_0 \rVert_2^2$ and so on. The total kinetic energy is \begin{equation} \color{#2ca02c}{T} = \sum_{i=0}^1 \frac{1}{2} m \, v_i^\top v_i = \sum_{i=0}^1 \frac{1}{2} v_i^\top \begin{pmatrix} m & 0 & 0\\\ 0 & m & 0\\\ 0 & 0 & m \end{pmatrix} v_i = \frac{1}{2} \dot q^\top \color{#2c3e50}{M} \, \dot q, \end{equation} where $\color{#2c3e50}{M}$ is the block diagonal mass matrix with two $3\times 3$ particle mass matrices on the diagonal, so $M \in \mathbb{R}^{6\times 6}$.

For potential energy we want:

- the spring should return to its rest length when all external forces are removed

- rigid motions should not change energy

- energy should depend only on particle positions

We first define the strain, \(\underbrace{\color{#17becf}{\ell}}_{\color{#17becf}{\text{deformed length}}}-\overbrace{\color{#008080}{\ell_0}}^{\color{#008080}{\text{rest length}}}\). However, $\ell=\ell_0$ is not a global minimum, so define potential energy as $\tfrac{1}{2}k(\ell-\ell_0)^2$, where $k$ is a stiffness parameter. To define the length we have

\begin{equation}

\Delta x = x_1-x_0 = \underbrace{\begin{pmatrix}

-\mathbb{I} \; & \; \mathbb{I}

\end{pmatrix}}_{B} \overbrace{\begin{pmatrix}

x_0 \\\\ x_1

\end{pmatrix}}^{q} \;\implies\; \ell = \sqrt{\Delta x^\top \Delta x} = \sqrt{q^\top B^\top B q}.

\end{equation}

Thus, the Lagrangian looks like

\begin{equation}

L = \frac{1}{2} \dot q^\top M \, \dot q - \frac{1}{2} k\left(\sqrt{q^\top B^\top B q} - \color{#008080}{\ell_0}\right)^2.

\end{equation}

Our Euler–Lagrange equation simplifies since only $V$ depends on $q$:

\begin{equation}

\frac{d}{dt}\frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot q} = -\frac{\partial V}{\partial q} \;\triangleq\; f(q).

\end{equation}

We can simplify the left-hand side as

\begin{equation}

\begin{split}

\frac{d}{dt}\frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot q} &= \frac{d}{dt}\frac{\partial}{\partial \dot q}\left(\frac{1}{2}\, \dot q^\top M \, \dot q\right) \\\

&= \frac{d}{dt}\, (M\, \dot q) \\\

&= M \, \ddot q \quad \text{(since $M$ is constant)} \\\

\implies\quad \color{#2c3e50}{M}\, \color{#d62728}{\ddot q} &= -\frac{\partial V}{\partial q}.

\end{split}

\end{equation}

Representing Meshes

To represent a mesh we can think of each vertex as a mass and each edge as a spring. The block diagonal mass for the entire mesh is

\begin{equation}

\color{#2c3e50}{M} = \begin{pmatrix}

M_0 & \cdots & 0 \\\

\vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\\

0 & \cdots & M_{n-1}

\end{pmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{3n \times 3n}.

\end{equation}

We can compute kinetic and potential energies by summing over all individual energies. Define $q_j$ as

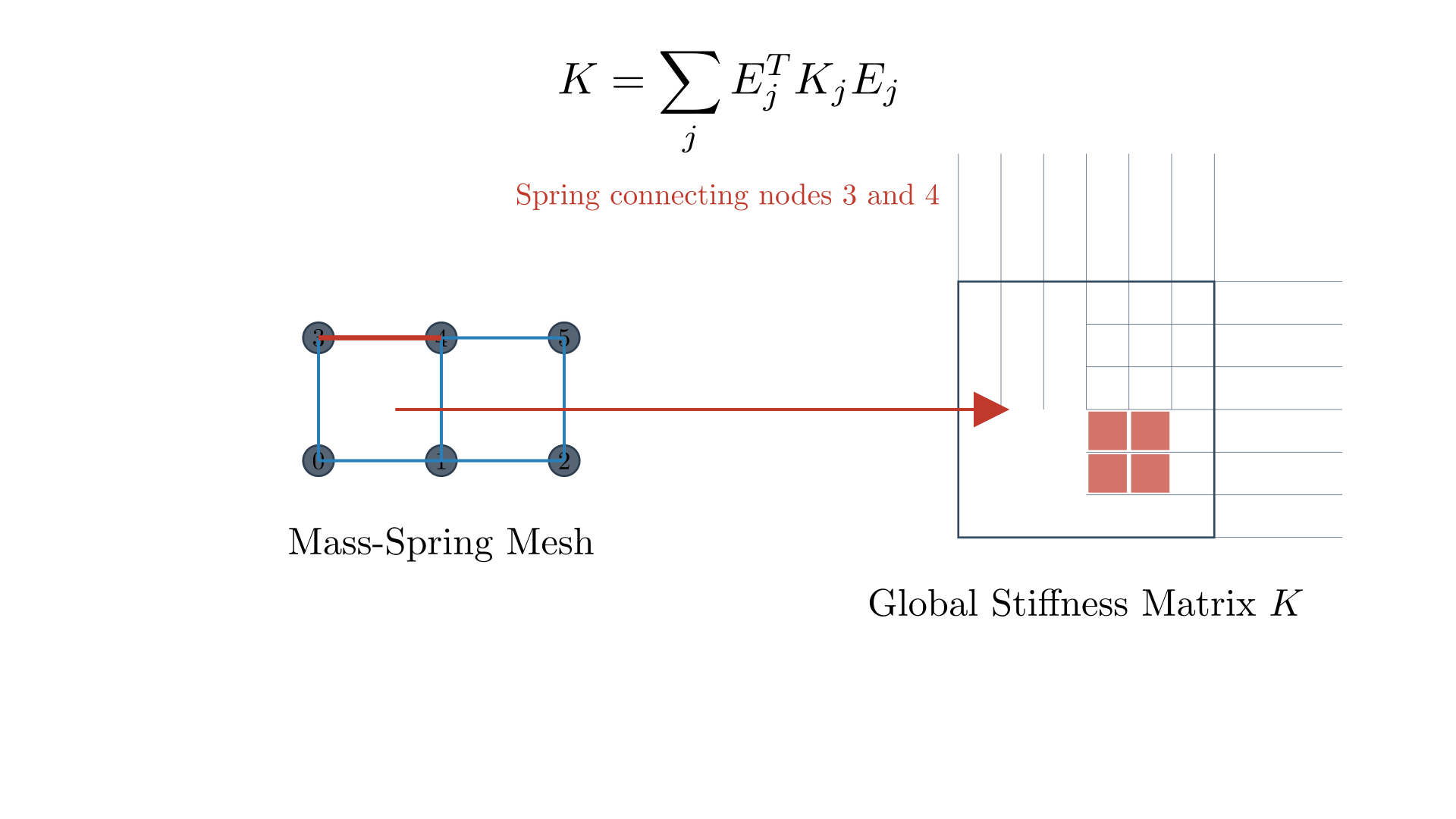

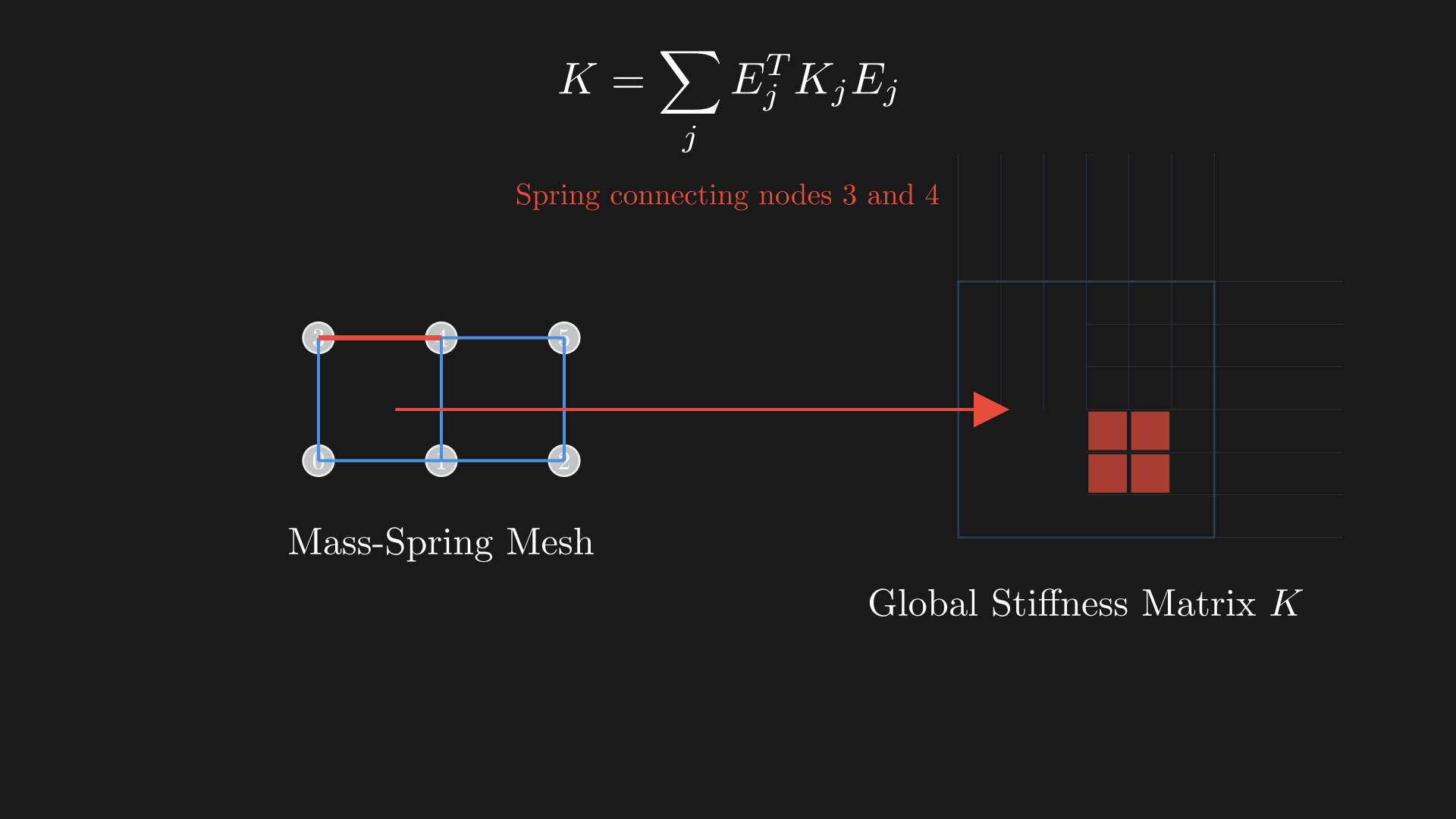

Here, $\color{#8c564b}{E_j}$ is a binary selection (gather) matrix that extracts the two endpoints of spring $j$ from the global vector $q$.14

So our Lagrangian for a mesh looks like \begin{equation} L = \frac{1}{2}\, \dot q^\top M \, \dot q - \sum_{j=0}^{m-1} V_j(E_j q). \end{equation} We can compute the generalized forces as

\[\begin{equation} \begin{split} -\frac{\partial V}{\partial q} &= -\frac{\partial}{\partial q} \sum_{j=0}^{m-1} V_j(E_j q) \\ &= - \sum_{j=0}^{m-1} E_j^T \frac{\partial V_j}{\partial q_j}(q_j) \;\underbrace{(q_j)}_{\text{per-spring gradient}} \\ &= \sum_{j=0}^{m-1} E_j^T f_j(q_j) \;\underbrace{(q_j)}_{\text{per-spring generalized force}}. \end{split} \end{equation}\]Linearly-Implicit Time Integration

We will start with Backward Euler:

\(\begin{equation} \begin{split} M\dot{q}^{\, t+1} &= M\dot{q}^{\, t} + \Delta t\, f(q^{t+1}) \quad\; \text{(Backward Euler)}, \\ q^{t+1} &= q^t + \Delta t\, \dot{q}^{\, t+1}, \\ M\dot{q}^{\, t+1} &= M\dot{q}^{\, t} + \Delta t\, f(\underbrace{q^t + \Delta t\, \dot{q}^{\, t+1}}_{\text{Substitute}}), \\ M\dot{q}^{\, t+1} &\approx M\dot{q}^{\, t} + \Delta t\, f(q^t) + \underbrace{\Delta t^2 \, \frac{\partial f}{\partial q}\, \dot{q}^{\, t+1}}_{\text{stiffness matrix }\, \color{#c0392b}{K}} \quad \text{(first order)}, \\ (M - \Delta t^2 K)\, \dot{q}^{\, t+1} &= M\dot{q}^{\, t} + \Delta t\, f(q^t) \quad \text{(solve linear system)}, \\ q^{t+1} &= q^t + \Delta t\, \dot{q}^{\, t+1} \quad \text{(update position)}. \end{split} \end{equation}\) This is a first-order linearization of the force map around $q^t$.15

We still need to figure out the stiffness matrix $\color{#c0392b}{K}$,16

\begin{equation}

\begin{split}

K &= \frac{\partial f}{\partial q} \quad \text{(by definition)},\\\

\; f &= -\frac{\partial}{\partial q} \sum_{j=0}^{m-1} V_j(E_j q),\\\

\color{#c0392b}{K} &= -\frac{\partial^2}{\partial q^2} \sum_{j=0}^{m-1} V_j(E_j q)\\\

&= -\sum_{j=0}^{m-1} \frac{\partial^2}{\partial q^2} V_j(E_j q)\\\

&= \sum_{j=0}^{m-1} \left(-E_j^T \frac{\partial^2 V_j}{\partial q_j^2} E_j\right)\\\

&= \sum_{j=0}^{m-1} \left(E_j^T \color{#c0392b}{K_j} E_j\right).

\end{split}

\end{equation}

So $K$ is the negative Hessian (matrix of second derivatives) of the potential energy. A per-spring stiffness matrix is

\begin{equation}

\color{#c0392b}{K_j} = -\frac{\partial^2 V_j}{\partial q_j^2}.

\end{equation}

The individual stiffness matrix is $12\times 12$ and is assembled as in the figure.

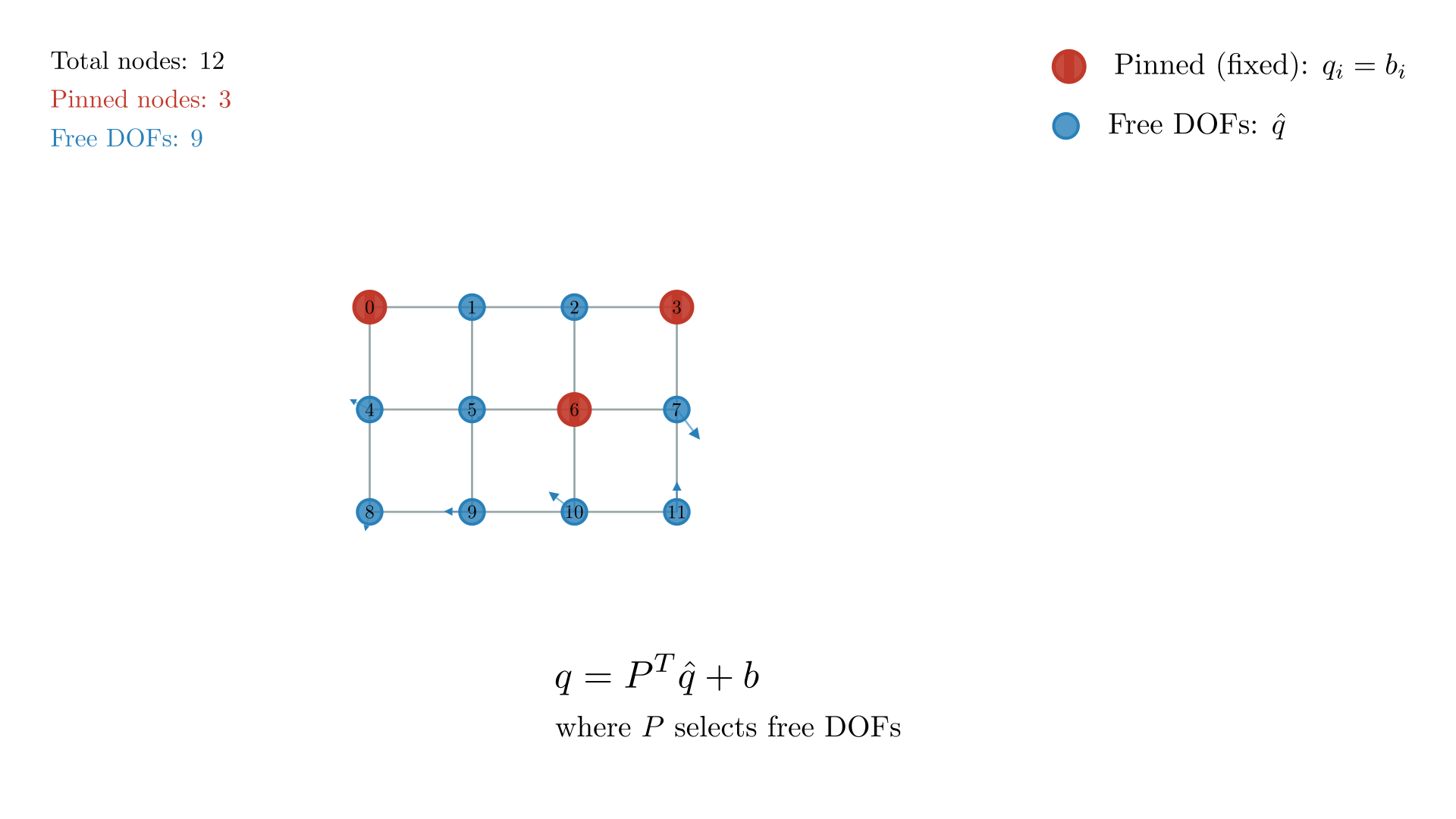

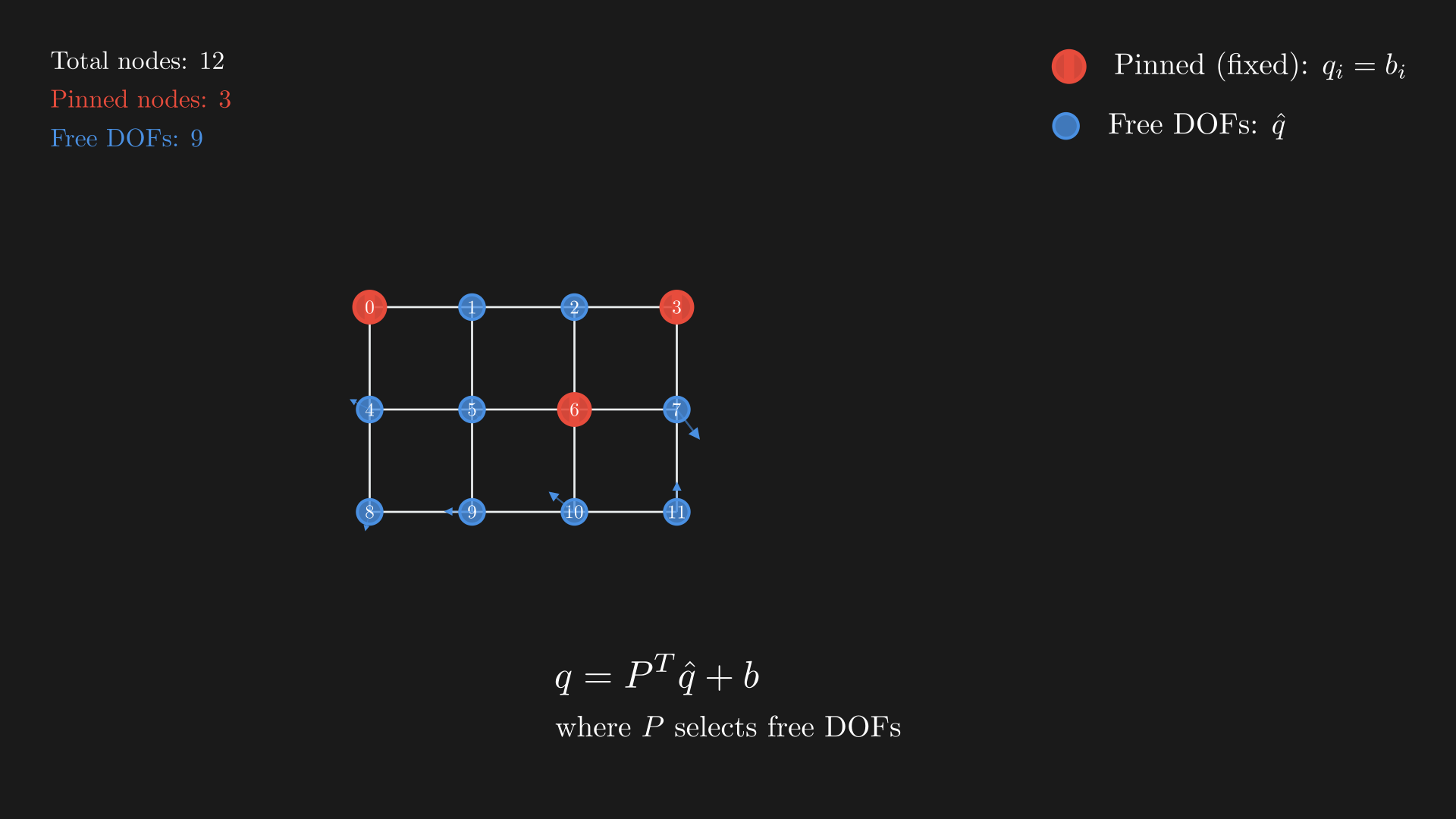

How to Add Constraints

We may want invisible constraints like fixing the position of certain vertices (red dots in our demo) so they can never move. To enforce $q_i = b_i$, define a reduced set of DOFs17

Then

\begin{equation}

P^T\hat{q} = \overbrace{\begin{pmatrix}

x_0 \\

x_1 \\

x_2 \\

0 \\

\vdots \\

x_n

\end{pmatrix} +

\underbrace{\begin{pmatrix}

0 \\

0 \\

0 \\

\color{#e67e22}{b_i} \\

\vdots \\

0

\end{pmatrix}}_{\color{#e67e22}{b}}}^{q}.

\end{equation}

Thus, with $q=P^T\hat{q} + \color{#e67e22}{b}$ and $\dot q = P^T \dot{\hat{q}}$ we get

\begin{equation}

\begin{split}

P\left(M - \Delta t^2 K\right)P^T\, \dot{\hat{q}}^{\, t+1} &= P M\, \dot{q}^{\, t} + \Delta t\, P f(q^t), \\\

q^{t+1} &= q^t + \Delta t\, P^T \dot{\hat{q}}^{\, t+1}.

\end{split}

\end{equation}

Citation

Please cite this work as:

Rishit Dagli. "Hopefully the Most Gentle Introduction to Simulation". Rishit Dagli's Blog (September 2025). https://rishit-dagli.github.io/2025/09/18/simulation.htmlOr use the BibTex citation:

@article{ dagli2025hopefully,

title = { Hopefully the Most Gentle Introduction to Simulation },

author = { Rishit Dagli },

journal = {rishit-dagli.github.io},

year = { 2025 },

month = { September },

url = "https://rishit-dagli.github.io/2025/09/18/simulation.html"

}References and Footnotes

-

A common example of state is when we consider a particle with some motion, we not only need to know its position but also its momentum to know the state. ↩

-

Now, if you think about the geometry of the space of all states, it is natural to ask if this space is continous or discrete, after all we are working with meshes? In mechanics, we (usually) assume a smooth configuration space (a continuous set of positions and orientations) or a smooth manifold. If you don’t assume a $C^\infty$ smooth world, we get some weird things best left to later. So what are we doing in simulation? In graphics, when we implement things, configurations spaces don’t really stay smooth, but you should think of it as we are working in a smooth world but just have a discrete surrogate we apply the results on. ↩

-

Vectorial mechanics writes equations directly in terms of forces and accelerations ($F=ma$). Variational (analytical) mechanics specifies a scalar Lagrangian $L=T-V$ and chooses trajectories that make the action $S=\int L\,dt$ stationary. For conservative systems these formalisms are equivalent via the Euler–Lagrange equations. ↩

-

In general, contrary to this blog, I like the Hamiltonian way of looking at things a lot. So, I like to think of generalized coordinates as parametrizing the configuration manifold $X$ (e.g., particle positions). A mapping $f: q \mapsto x$ embeds these into world coordinates. ↩

-

The Jacobian $\color{#8c564b}{J}=\tfrac{df}{dq}$ maps generalized velocities to world velocities: $\color{#1f77b4}{\dot x} = \color{#8c564b}{J}(q)\,\color{#1f77b4}{\dot q}$. If $q\in\mathbb{R}^m$ and $x\in\mathbb{R}^n$, then $\color{#8c564b}{J}\in\mathbb{R}^{n\times m}$. ↩

-

$SO(3)$ is the group of $3\times3$ rotation matrices with $R^\top R=I$ and $\det R=1$; it represents rigid-body rotations in 3D. ↩

-

Hamilton’s principle (stationary action) states that the physical trajectory $q(t)$ makes $S(q,\dot q)=\int_{t_1}^{t_2}(T-V)\,dt$ stationary under variations that fix the endpoints $q(t_1),q(t_2)$. ↩

-

The first variation $\delta S$ is the directional derivative of the functional $S$ along a perturbation $\delta q$. Setting $\delta S=0$ for all admissible $\delta q$ yields the Euler–Lagrange equations. ↩

-

The Euler–Lagrange equation $\tfrac{d}{dt}\tfrac{\partial L}{\partial \dot q}=\tfrac{\partial L}{\partial q}$ is the necessary condition for $S$ to be stationary. With $L=T-V$ and $T=\tfrac12\dot q^\top M\dot q$, it recovers Newton’s second law. ↩

-

In general, contrary to this blog, I like the Hamiltonian way of looking at things a lot. The phase plane here is $(q,v)$. More generally, the state (phase) space is the cotangent bundle $M=T^*X$ with a symplectic form $\omega$; dynamics are flows of vector fields on $M$. ↩

-

For oscillatory systems with purely imaginary eigenvalues, Forward Euler’s amplification factor exits the unit circle, causing energy growth. For the test equation $y’=\lambda y$ with $\Re(\lambda)<0$, Forward Euler is stable only if $\mid1+\lambda\Delta t\mid<1$. ↩

-

Runge–Kutta methods are single-step integrators that form weighted averages of slopes $f(\cdot)$ evaluated at intermediate states; RK2 (Heun) and RK4 are common choices. ↩

-

Backward Euler is A-stable (unconditionally stable for linear problems) and numerically dissipative: it damps energy even for undamped oscillators, which can be desirable when modeling real damping. ↩

-

A selection (gather) matrix $E_j$ picks the DOFs used by spring $j$ from the global vector $q$; its transpose $E_j^T$ scatters per-spring forces back to the global force vector. ↩

-

Replace $f(q^{t+1})$ with a first-order Taylor expansion about $q^t$: $f(q^{t+1})\approx f(q^t)+\tfrac{\partial f}{\partial q}\,(q^{t+1}-q^t)$, yielding a linear system each step. ↩

-

Using $f(q)=-\tfrac{\partial V}{\partial q}$, the tangent stiffness is $K=\tfrac{\partial f}{\partial q}=-\tfrac{\partial^2 V}{\partial q^2}$, i.e., the negative Hessian of the potential. ↩

-

Eliminating fixed DOFs via a reduced coordinate map $q=P^\top\hat q + b$ enforces hard constraints exactly while solving only for free DOFs $\hat q$. P selects non-fixed rows of the identity; b carries the fixed values. ↩