SEE-2-SOUND🔉: Zero-Shot Spatial Environment-to-Spatial Sound

In this blog post, I will introduce our recent work, SEE-2-SOUND 1. I will try to explain intuitively the motivation behind our work, how I ended up thinking of this idea, explain how the method works, discuss some subtle aspects of our implementation, and discuss some future prospects.

While this does sound like everything that should be in our paper (and it is in our paper), I will try to keep this announcement blog post for the most part very intuitive and try to talk about things not in our paper.

Motivation

Text-to-image 2\(^,\)3\(^,\)4\(^,\)5\(^,\)6 and text-to-video 7\(^,\)8\(^,\)9\(^,\)10\(^,\)11\(^,\)12\(^,\)13\(^,\)14\(^,\)15\(^,\)16\(^,\)17 are some of the most popular areas of research in machine learning. Text-to-audio 18\(^,\)19\(^,\)20\(^,\)21\(^,\)22 (not to be confused with text-to-speech), while not as popular as the aforementioned areas have also had quite a few papers. Finally, the image to audio 23\(^,\)24\(^,\)25 space has been very underexplored but there still have been a few works in this area.

I had two main thoughts:

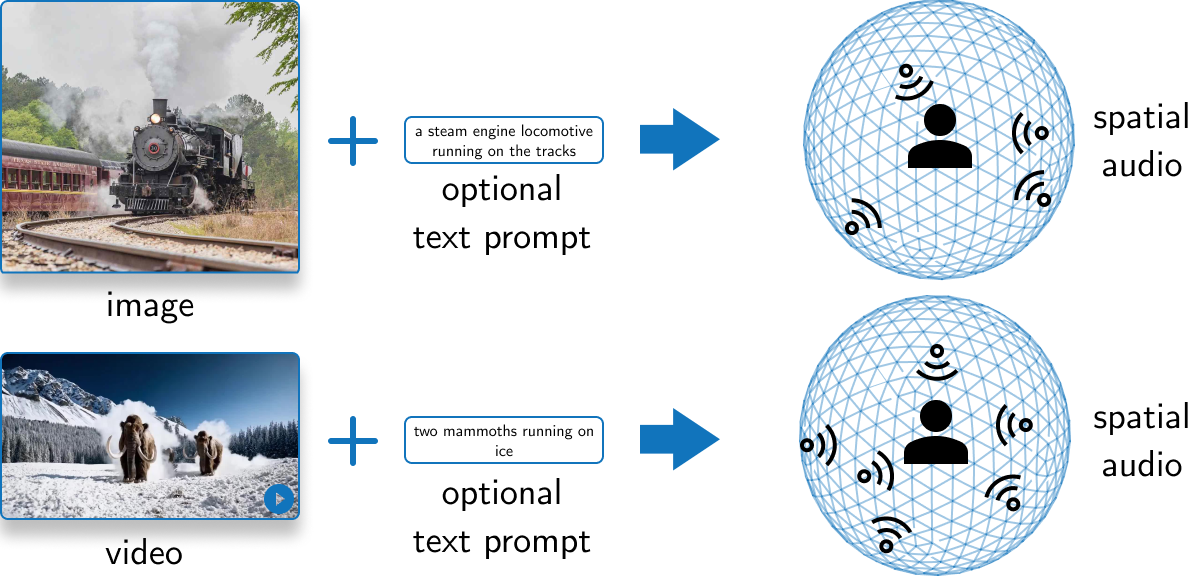

- one of the things I was interested in was being able to do joint generation i.e. do either: text to image + audio or text to video + audio

- even if you do manage to do joint generation; as someone who uses spatial audio earphones every day, there seems to be an evident qualitative gap in generating natural-like audio: spatial audio. Humans in general have an exciting capability of pinpointing the location of an object by just hearing it and any generated audio should be able to generate this perception too.

After these thoughts, I ran some experiments just for fun and ended up with very bad results just trying to learn a joint embedding space with CLIP 26 and CLAP 27 style training. Around this time, I was talking to some other students at UofT when I thought it might be interesting to work on image/video to spatial sound to make a step towards truly complete generation.

How does SEE-2-SOUND work?

One of the goals of this announcement blog post is to also give a simple informal explanation about how our method works.

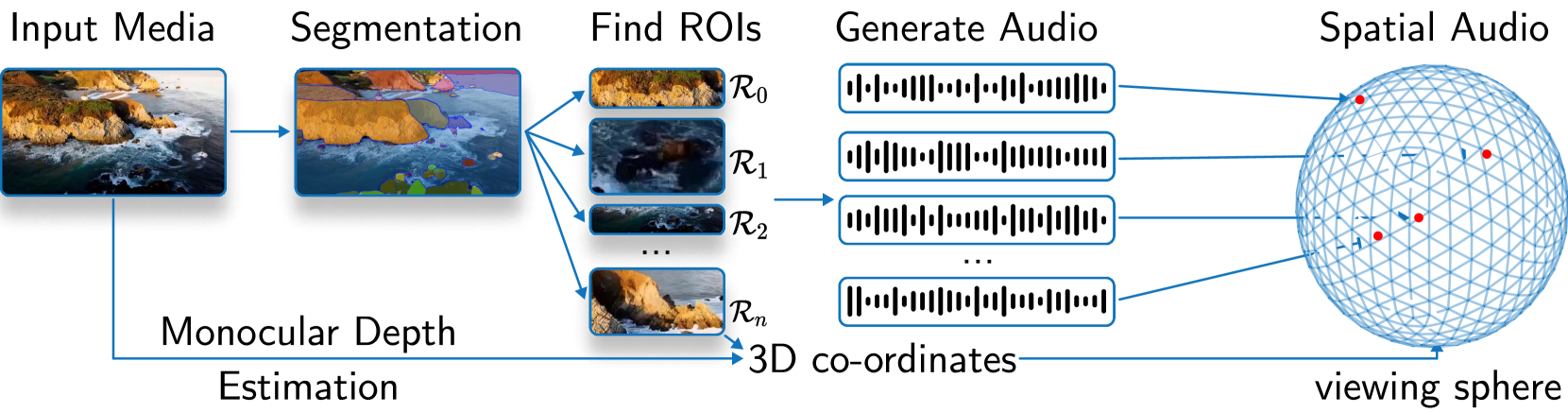

The SEE-2-SOUND pipeline can broadly be composed of multiple problems:

- find the main regions of interest in a video or image

- estimate 3D positions of these regions of interest

- generate multiple mono audios

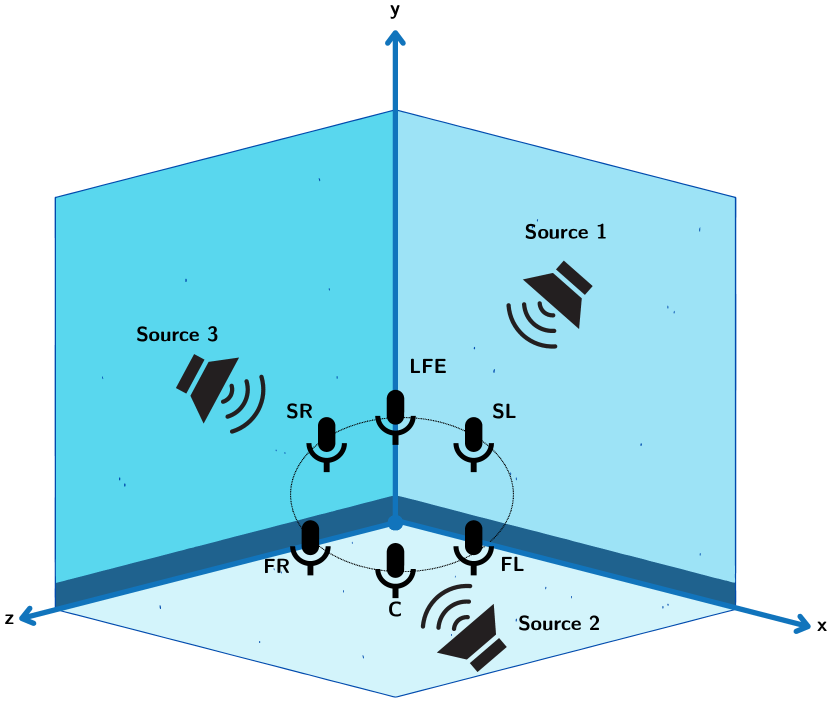

- put together mono audios from step 3 and positions from step 2 to make spatial audio

Precisely, for the first step, we perform segmentation and estimate 2D coordinates for each ROIs. For the second step, we perform depth estimation to estimate 3D coordinates for each ROI. For the third step, we generate mono audio conditioned on each ROI and text. Finally, we place all of these audio according to the 3D coordinates and modify these coordinates to place them on a viewing sphere and simulate the generation of spatial or surround sound.

Evaluation

It is very hard to evaluate this approach as there is no direct way to evaluate spatial audio generation. We have to rely on indirect metrics like the marginal scene guidance which is also hard to somehow measure. So, we develop ways to evaluate our approach:

- we perform an in-depth human evaluation study and analyze our method by performing \(\chi^2\)-tests at \(p < 0.05\)

- we also propose a new evaluation protocol that measures marginal scene guidance

Particularly, for human evaluation we task the human evaluators with performing:

- Spatial audio quality: Human evaluators qualitatively rate the realism, immersion, and accuracy of two images or videos with spatial audio generated by our method. These aspects are measured using a semantic differential scale (i.e. rate from 1-5).

- Audio identification: Evaluators estimate the sensation of direction and distance of an object given the generated spatial audio.

- Adversarial identification: Evaluators are given a random mix of generated spatial audios and mono audios. They are tasked with discriminating whether the given audio is indeed spatial audio, their accuracy is measured.

- Audio matching: Evaluators are provided with three clips of spatial audio and three images or videos. They perform a matching task to pair the audio clips with the corresponding visual content, and their matching accuracy is measured.

We notice that our approach performs well on all of these tasks when performing \(\chi^2\)-tests.

Particularly, for our evaluation protocol, we generate audio from our method and baseline 23. We then use these audio outputs and images to generate modified scene-guided audio generated using AViTAR 28. AviTAR (or VAM) 28 takes in an audio file and modifies the audio to match the image. Now we take modified audio and audio (from our method and baseline) and measure the audio similarity of these. Notice, that if the similarity between two audio clips is less, then the audio is more scene-guided (or better). We notice that our method for the most part performs better than the baseline in this evaluation protocol.

Future Work

Although SEE-2-SOUND produces compelling spatial audio clips, there are several limitations and avenues for future work. First, our framework may not detect all of the fine details in images and videos, nor does it produce audio for every fine detail. If we try to produce audio for many fine structures with this framework using upscaling or other zooming-in methods, we observe a lot of interference within the audio.

Second, SEE-2-SOUND does not generate audio based on any motion cues but solely based on the image priors. We could benefit from having separate appearance and motion backbones, which may potentially allow us to use any motion information to refine the generated audio.

Third, currently, our method is not able to work in real-time on an Nvidia A100-80 GPU on which the experiments were conducted. However, since SEE-2-SOUND relies on composing off-the-shelf models, we could easily swap out the models we use for other models that solve the individual subproblems. We can easily incorporate advances in any of the subproblem areas within our framework to potentially get to real-time capabilities.

Lastly, inherent in the capabilities of generative models such as SEE-2-SOUND– which excel in producing synchronized and realistic outputs – is a significant concern regarding the potential generation and dissemination of deepfakes. The exploitation of this technology by malicious entities poses a notable risk even though we do not generate speech, as they could fabricate realistic counterfeit audio clips. We condemn any such applications and hope to be able to work on safeguards for such approaches in the future.

Relevant Links

I have noticed a few minor issues with the pip version of the codebase that you get with

pip install see2sound, and I am investigating this. However, cloning the repository and performing a local install work perfectly.

- Paper: arxiv.com

- Project website: github.io

- Code (public and open-source): github.com

- Demo: huggingface.com

- Demo (w/ caching to run the examples quickly by @jadechoghari): huggingface.com

I also want to thank HuggingFace especially Adina Yakefu, Ahsen Khaliq, Jade Choghari, Toshihiro Hayashi, Vaibhav Srivastav, and Yuvraj Sharma for featuring the paper, introducing me to building HF Spaces and also giving us access to ZERO GPU (check out HuggingFace ZERO GPU if you have not) to host the demo on HuggingFace.

Concluding Thoughts

Overall, we introduce a method for generating spatial sound from images and videos. We envision many avenues for potential impact based on our technique, including applications related to enhancing images and videos generated by learned methods, making real images interactive, human-computer interaction problems, or accessibility. I am also quite glad to work on a problem that does spatial audio generation and makes a step towards truly complete generation while being zero-shot. To the best of my knowledge, our approach is also the first to generate spatial audio from images and videos.

In general, while I do think composition is an interesting way of going about learning algorithms due to the popular works 29\(^,\)30\(^,\)31\(^,\)32 but the composition doesn’t work for all kinds of problems. For example, a lot of capabilities that require multiple specialized LLMs would soon be significantly disrupted since models seem to keep getting better at the moment.

While the method can be applied to add sound to real or AI-generated visual content, I am personally very excited to see this be paired with a video generation model and hope that the future works we inspire lead to the generation of truly immersive digital content.

References

-

Dagli, R., Prakash, S., Wu, R., & Khosravani, H. (2024). SEE-2-SOUND: Zero-Shot Spatial Environment-to-Spatial Sound. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.06612. ↩

-

Rombach, R., Blattmann, A., Lorenz, D., Esser, P., & Ommer, B. (2022). High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 10684-10695). ↩

-

Podell, D., English, Z., Lacey, K., Blattmann, A., Dockhorn, T., Müller, J., … & Rombach, R. (2023). Sdxl: Improving latent diffusion models for high-resolution image synthesis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.01952. ↩

-

Saharia, C., Chan, W., Saxena, S., Li, L., Whang, J., Denton, E. L., … & Norouzi, M. (2022). Photorealistic text-to-image diffusion models with deep language understanding. Advances in neural information processing systems, 35, 36479-36494. ↩

-

Ramesh, A., Pavlov, M., Goh, G., Gray, S., Voss, C., Radford, A., … & Sutskever, I. (2021, July). Zero-shot text-to-image generation. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 8821-8831). Pmlr. ↩

-

Ramesh, A., Dhariwal, P., Nichol, A., Chu, C., & Chen, M. (2022). Hierarchical text-conditional image generation with clip latent. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.06125, 1(2), 3. ↩

-

Ho, J., Salimans, T., Gritsenko, A., Chan, W., Norouzi, M., & Fleet, D. J. (2022). Video diffusion models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35, 8633-8646. ↩

-

Ho, J., Chan, W., Saharia, C., Whang, J., Gao, R., Gritsenko, A., … & Salimans, T. (2022). Imagen video: High-definition video generation with diffusion models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.02303. ↩

-

Singer, U., Polyak, A., Hayes, T., Yin, X., An, J., Zhang, S., … & Taigman, Y. (2022). Make-a-video: Text-to-video generation without text-video data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.14792. ↩

-

Zhang, Y., Wei, Y., Jiang, D., Zhang, X., Zuo, W., & Tian, Q. (2023). Controlvideo: Training-free controllable text-to-video generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.13077. ↩

-

Khachatryan, L., Movsisyan, A., Tadevosyan, V., Henschel, R., Wang, Z., Navasardyan, S., & Shi, H. (2023). Text2video-zero: Text-to-image diffusion models are zero-shot video generators. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (pp. 15954-15964). ↩

-

Wu, J. Z., Ge, Y., Wang, X., Lei, S. W., Gu, Y., Shi, Y., … & Shou, M. Z. (2023). Tune-a-video: One-shot tuning of image diffusion models for text-to-video generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (pp. 7623-7633). ↩

-

Blattmann, A., Rombach, R., Ling, H., Dockhorn, T., Kim, S. W., Fidler, S., & Kreis, K. (2023). Align your patients: High-resolution video synthesis with latent diffusion models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 22563-22575). ↩

-

Blattmann, A., Dockhorn, T., Kulal, S., Mendelevitch, D., Kilian, M., Lorenz, D., … & Rombach, R. (2023). Stable video diffusion: Scaling latent video diffusion models to large datasets. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.15127. ↩

-

Esser, P., Chiu, J., Atighehchian, P., Granskog, J., & Germanidis, A. (2023). Structure and content-guided video synthesis with diffusion models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (pp. 7346-7356). ↩

-

Bar-Tal, O., Chefer, H., Tov, O., Herrmann, C., Paiss, R., Zada, S., … & Mosseri, I. (2024). Lumiere: A space-time diffusion model for video generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.12945. ↩

-

Brooks, T., Peebles, B., Homes, C., DePue, W., Guo, Y., Jing, L., … & Ramesh, A. (2024). Video generation models as world simulators. ↩

-

Liu, H., Chen, Z., Yuan, Y., Mei, X., Liu, X., Mandic, D., … & Plumbley, M. D. (2023). Audioldm: Text-to-audio generation with latent diffusion models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.12503. ↩

-

Liu, H., Yuan, Y., Liu, X., Mei, X., Kong, Q., Tian, Q., … & Plumbley, M. D. (2024). Audioldm 2: Learning holistic audio generation with self-supervised pretraining. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing. ↩

-

Huang, R., Huang, J., Yang, D., Ren, Y., Liu, L., Li, M., … & Zhao, Z. (2023, July). Make-an-audio: Text-to-audio generation with prompt-enhanced diffusion models. In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 13916-13932). PMLR. ↩

-

Borsos, Z., Marinier, R., Vincent, D., Kharitonov, E., Pietquin, O., Sharifi, M., … & Zeghidour, N. (2023). Audiolm: a language modeling approach to audio generation. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing. ↩

-

Kreuk, F., Synnaeve, G., Polyak, A., Singer, U., Défossez, A., Copet, J., … & Adi, Y. (2022). Audiogen: Textually guided audio generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.15352. ↩

-

Tang, Z., Yang, Z., Zhu, C., Zeng, M., & Bansal, M. (2024). Any-to-any generation via composable diffusion. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36. ↩ ↩2

-

Tang, Z., Yang, Z., Khademi, M., Liu, Y., Zhu, C., & Bansal, M. (2024). CoDi-2: In-Context Interleaved and Interactive Any-to-Any Generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 27425-27434). ↩

-

Sheffer, R., & Adi, Y. (2023, June). I hear your true colors: Image-guided audio generation. In ICASSP 2023-2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) (pp. 1-5). IEEE. ↩

-

Radford, A., Kim, J. W., Hallacy, C., Ramesh, A., Goh, G., Agarwal, S., … & Sutskever, I. (2021, July). Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 8748-8763). PMLR. ↩

-

Radford, A., Kim, J. W., Hallacy, C., Ramesh, A., Goh, G., Agarwal, S., … & Sutskever, I. (2021, July). Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 8748-8763). PMLR. ↩

-

Chen, C., Gao, R., Calamia, P., & Grauman, K. (2022). Visual acoustic matching. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 18858-18868). ↩ ↩2

-

Liu, N., Li, S., Du, Y., Torralba, A., & Tenenbaum, J. B. (2022, October). Compositional visual generation with composable diffusion models. In European Conference on Computer Vision (pp. 423-439). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. ↩

-

Okawa, M., Lubana, E. S., Dick, R., & Tanaka, H. (2024). Compositional abilities emerge multiplicatively: Exploring diffusion models on a synthetic task. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36. ↩

-

Su, J., Liu, N., Wang, Y., Tenenbaum, J. B., & Du, Y. Compositional Image Decomposition with Diffusion Models. In Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning. ↩

-

Ling, W., Luís, T., Marujo, L., Astudillo, R. F., Amir, S., Dyer, C., … & Trancoso, I. (2015). Finding function in form: Compositional character models for open vocabulary word representation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1508.02096. ↩