Plant AI: Student Ambassador Green-A-Thon activity report

Hello developers 👋! In this article, we introduce our project “Plant AI ☘️” and walk you through our motivation behind building this project, how it could be helpful to the community, the process of building this project, and finally our future plans with this project.

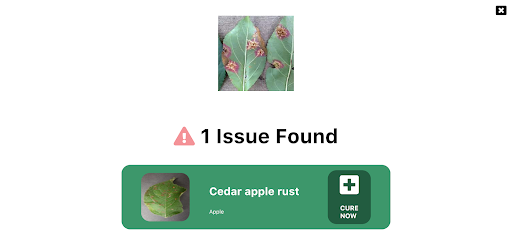

Plant AI ☘️ is a web application 🌐 that helps to easily diagnose diseases in plants from plant images using Machine Learning available on the web. We provide an interface on the website where you can upload images of your plant leaves. Since we focus on plant leaf diseases we can detect the plant’s diseases by seeing an image of the leaves. We also provide users easy ways to treat the diagnosed disease.

As of now, our model supports 38 categories of healthy and unhealthy plant images across species and diseases. See the complete list of supported diseases and species can be found here. If you are want to test out Plant AI, you can use one of these images.

Guess, what? This project is also completely open-sourced⭐, here is the GitHub repo for this project: https://github.com/Rishit-dagli/Greenathon-Plant-AI

The motivation behind building this

Human society needs to increase food production an estimated 70% by 2050 to feed an expected population size that is predicted to be over 9 billion people 1. Currently, infectious diseases reduce the potential yield by an average of 40% with many farmers in the developing world experiencing yield losses as high as 100%.

The widespread distribution of smartphones among farmers around the world offers the potential of turning smartphones into a valuable tool for diverse communities growing food.

Our motivation with Plant AI is to aid crop growers by turning their smartphones into a diagnosis tool that could substantially increase crop yield and reduce crop failure. We also aim to make this rather easy for crop growers so the tool can be used on a daily basis.

How does this work?

As we highlighted in the previous section, our main target audience with this project is crop growers. We intend for them to use this on a daily basis to diagnose disease from their plant images.

Our application relies on the Machine Learning Model we built to identify plant diseases from images. We first built this Machine Learning model using TensorFlow and Azure Machine Learning to keep track, orchestrate, and perform our experiments in a well-defined manner. A subset of our experiments used to build the current model have also been open-sourced and can be found on the project’s GitHub repo.

We were quite interested in running this Machine Learning model on mobile devices and smartphones to further amplify its use. Using TensorFlow JS to optimize our model allows it to work on the web for devices that are less compute-intensive.

We also optimized this model to work on embedded devices with TensorFlow Lite further expanding the usability of this project and also providing a hosted model API built using TensorFlow Serving and hosted with Azure Container Registry and Azure Container Instances.

We talk about the Machine Learning aspect and our experiments in greater detail in the upcoming sections.

To allow plant growers to easily use this Plant AI, we provide a fully functional web app built with React and hosted on Azure Static Web Apps. This web app allows farmers to use the Machine Learning model and identify diseases from plant images all on the web. You can try out this web app at https://www.plant-ai.tech/ and upload a plant image to our model. In case you want to test out the web app we also provide real-life plant images you can use.

We expect most of the traffic and usage of Plant AI from mobile devices, consequently, the Machine Learning model we run through the web app is optimized to run on the client-side.

This also enables us to have blazing fast performance with our ML model. We use this model on the client-side with TensorFlow JS APIs which also allows us to boost performance with a WebGL backend.

Building the Machine Learning Model

Building the Machine Learning Model is a core part of our project. Consequently, we spent quite some time experimenting and building the Machine Learning Model. We had to build a machine learning model that offers acceptable performance and is not too heavy since we want to run the model on low-end devices

Training the model

We trained our model on the Plant Village dataset 2 on about 87,000 (+ augmented images) healthy and unhealthy leaf images. These images were classified into 38 categories based on species and diseases. Here are a couple of images the model was trained on:

We experimented with quite a few architectures and even tried building our own architectures from scratch using Azure Machine Learning to keep track, orchestrate, and perform our experiments in a well-defined manner.

It turned out that transfer learning on top of MobileNet 3 was indeed quite promising for our use case. The model we built gave us the acceptable performance and was close to 12 megabytes in size, not a heavy one. Consequently, we built a model on top of MobileNet using initial weights from MobileNet trained on ImageNet 4.

We also made a subset of our experiments used to train the final model for public use through this project’s GitHub repository.

Running the model on a browser

We applied TensorFlow JS (TFLS) to perform Machine Learning on the client-side on the browser. First, we converted our model to the TFJS format with the TensorFlow JS converter, which allowed us to easily convert our TensorFlow SavedModel to TFJS format. The TensorFlow JS Converter also optimized the model for the web by sharding the weights into 4MB files so that they can be cached by browsers. It also attempts to simplify the model graph itself using Grappler such that the model outputs remain the same. Graph simplifications often include folding together adjacent operations, eliminating common subgraphs, etc.

After the conversion, our TFJS format model has the following files, which are loaded on the web app:

- model.json (the dataflow graph and weight manifest)

- group1-shard*of* (collection of binary weight files)

Once our TFJS model was ready, we wanted to run the TFJS model on browsers. To do so we again made use of the TensorFlow JS Converter that includes an API for loading and executing the model in the browser with TensorFlow JS 🚀. We were excited to run our model on the client-side since the ability to run deep networks on personal mobile devices improves user experience, offering anytime, anywhere access, with additional benefits for security, privacy, and energy consumption.

Designing the web app

One of our major aims while building Plant AI was to make high-quality disease detection accessible to most crop growers. Thus, we decided to build Plant AI in the form of a web app to make it easily accessible and usable by crop growers.

As mentioned earlier, the design and UX of our project are focused on ease of use and simplicity. The basic frontend of Plant AI contains just a minimal landing page and two other subpages. All pages were designed using custom reusable components, improving the overall performance of the web app and helping to keep the design consistent across the web app.

Building and hosting the web app

Once the UI/UX wireframe was ready and a frontend structure was available for further development, we worked to transform the Static React Application into a Dynamic web app. The idea was to provide an easy and quick navigation experience throughout the web app. For this, we linked the different parts of the website in such a manner that all of them were accessible right from the home page.

Once we can access the models we load them using TFJS converter model loading APIs by making individual HTTP(S) requests for loading the model.json file (the dataflow graph and weight manifest) and the sharded weight file in the mentioned order. This approach allows all of these files to be cached by the browser (and perhaps by additional caching servers on the internet) because the model.json and the weight shards are each smaller than the typical cache file size limit. Thus a model is likely to load more quickly on subsequent occasions.

We first normalize our images that is to convert image pixel values from 0 to 255 to 0 to 1 since our model has a MobileNet backbone. After doing so we resize our image to 244 by 244 pixels using nearest neighbor interpolation though our model works quite well on other dimensions too. After doing so we use the TensorFlow JS APIs and the loaded model to get predictions on plant images.

Hosting the web app we built was made quite easy for us using Azure Static Web Apps. This allowed us to easily set up a CI/ CD Pipeline and Staging slots with GitHub Actions (Azure’s Static Web App Deploy action) to deploy the app to Azure. With Azure Static Web Apps, static assets are separated from a traditional web server and are instead served from points geographically distributed around the world right out of the box for us. This distribution makes serving files much faster as files are physically closer to end users.

Future Ideas

We are always looking for new ideas and addressing bug reports from the community. Our project is completely open-sourced and we are very excited if you have feedback, feature requests, or bug reports apart from the ones we mention here. Please consider contributing to this project by creating an issue or a Pull Request on our GitHub repo!

One of the top ideas we are currently working on is transforming our web app into a progressive web app to allow us to take advantage of features supported by modern browsers like service workers and web app manifests. We are working on this to allow us to support:

- Offline mode

- Improve performance, using service workers

- Platform-specific features, which would allow us to send push notifications and use location data to better help crop growers

- Considerably less bandwidth usage

- We are also quite interested in pairing this with existing on-field cameras to make it more useful for crop growers. We are exploring adding accounts and keeping a track of images the users have run on the model. Currently, we do not store any info about the images uploaded. It would be quite useful to track images added by farmers and store information about disease statistics in a designated piece of land on which we could model our suggestions to treat the diseases.

Thank you for reading!

If you find our project useful and want to support us; consider giving a star ⭐ on the project’s GitHub repo.

Many thanks to Ali Mustufa Shaikh and Jen Looper for helping me to make this better. :)

References

-

Alexandratos, Nikos, and Jelle Bruinsma. “World Agriculture towards 2030/2050: The 2012 Revision.” AgEcon Search, 11 June 2012, doi:10.22004/ag.econ.288998. ↩

-

Hughes, David P., and Marcel Salathe. “An Open Access Repository of Images on Plant Health to Enable the Development of Mobile Disease Diagnostics.” ArXiv:1511.08060 [Cs], Apr. 2016. arXiv.org, http://arxiv.org/abs/1511.08060. ↩

-

Howard, Andrew G., et al. “MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications.” ArXiv:1704.04861 [Cs], Apr. 2017. arXiv.org, http://arxiv.org/abs/1704.04861. ↩

-

Russakovsky, Olga, et al. “ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge.” ArXiv:1409.0575 [Cs], Jan. 2015. arXiv.org, http://arxiv.org/abs/1409.0575. ↩